With new technology, smarter tools, and a lot of patient digging, historians and archaeologists are uncovering marvels from every corner of the world.

One day it’s an enormous thigh bone from a titanosaur. Another day, Roman mosaics reappear from the waters of the Euphrates, still stunning after 2,000 years.

The world is full of wonders whether it’s ancient, modern, natural, or man-made, and so is this list curated from the Facebook group ‘Art, History & Archeology from around the world.’

Created in 2020, the group has grown to over 125.3K members.

#1

Roman mosaics re-emerged still intact from the waters of the Euphrates after 2000 years, Zeugma, Turchia.

© Photo: Pierangelo Piacentini

#2

In France, there’s a road called ‘Passage du Gois’ that seems to have a mind of its own. Twice a day, it disappears under 13 feet of water, only to reappear a few hours later.

If you want to cross it, you have to be quick, or the sea will rise and swallow it up again! It’s like something out of a fairy tale, but it’s real, and people still use it, if they dare!

© Photo: Pierangelo Piacentini

#3

These chandeliers are made from salt crystals.

Located 101 meters below the surface, Saint Kinga’s Chapel is an underground jewel in the Wieliczka Salt Mine in Krakow, Poland.

With impressive dimensions of 12 meters high, 18 meters wide and 54 meters long, this chapel is one of the main attractions of the mine, known for its magnificence and history.

Built over approximately 70 years, the chapel features a floor carved from a single block of salt and a ceiling adorned with luxurious chandeliers made from salt crystal, providing a unique and stunning atmosphere. Wieliczka gray salt, discovered in the 13th century, played a vital role in the medieval Polish economy, boosting trade and wealth for many noble and merchant families.

The Wieliczka Salt Mine is an underground labyrinth that spans nine levels, with the maximum depth reaching 327 meters. With more than 300 km of galleries and 3000 caves, the mine is a testament to human ingenuity over the centuries. In addition to Saint Kinga’s Chapel, visitors can explore churches, chapels and an impressive collection of mining tools at the Cracovian Saltworks Museum.

The historical and architectural richness of the Wieliczka Salt Mine was recognized by UNESCO in 1978, when it was officially designated a World Heritage Site, highlighting its cultural value and exceptional preservation over the centuries. This unique destination attracts visitors from around the world, offering an unforgettable experience of natural beauty and underground cultural heritage.

© Photo: Pierangelo Piacentini

Nothing has quite topped the spectacle of the opening of Tutankhamun’s tomb in 1922 or excavation of Troy in the 19th century.

And you might think that by now, we’d have already found most of the world’s great treasures, especially with high-tech tools like DNA analysis, satellite imaging, and 3D scanning making it easier than ever.

But over the past decade alone, archaeologists have uncovered discoveries that’ve changed how we look at the past.

Even King Tut keeps spilling secrets, like the fact that his famous dagger was forged from a meteorite that fell from the sky and we came to know about it only in 2016.

#4

The Basilica Cistern, located beneath the streets of Istanbul, Turkey, is a remarkable underground water storage facility dating back to the 6th century. Famous for its impressive collection of marble columns, this reservoir was initially constructed to supply water to the Great Palace of the Byzantine Empire. Today, it stands as a captivating historical attraction, inviting visitors to explore and appreciate the city’s deep-rooted heritage and remarkable architectural achievements.

© Photo: Alex Carter

#5

Here, alongside Sir David Attenborough, is an enormous thigh bone from a titanosaur, one of the most massive dinosaurs known to have roamed the Earth. This remarkable femur, measuring 2.4 meters (8 feet) in length, was unearthed in 2013 by a shepherd in the Chubut Province of Argentina, prompting a major excavation at La Flecha farm. During this dig, paleontologists found over 220 bones associated with at least seven individual titanosaurs, indicating a dinosaur that reached approximately 37 meters (121 feet) in length and weighed about 70 tonnes (154,000 pounds). Dating back nearly 100 million years, this titanosaur is regarded as the largest species identified to date, providing a fascinating insight into the giants of our planet’s distant past.

© Photo: Vlad Diaconu

#6

Deep in the heart of Libya’s Tadrart Acacus Desert lies the “Valley of the Planets,” a landscape that seems otherworldly.

Scattered throughout the valley are large, disc-like boulders that seem almost out of place among the typical desert rocks. Their smooth, rounded shapes are believed to have been shaped by millions of years of wind erosion, although their precise formation remains a topic of curiosity.

Some think these boulders may be remnants of an ancient geological formation, while others wonder whether unique desert conditions have shaped them over time. Due to Libya’s political situation and the valley’s isolation, scientific studies have been limited. So, for now, the mystery of how these disc-like stones came to be still lingers in the desert air.

© Photo: Pierangelo Piacentini

Even now, there are tons of secrets still buried on our planet.

Scientists are still mapping extensive cave networks and microclimates around the world, that could give us clues about new species or fossils.

Or even Stonehenge, for example, was created 5,000 years ago but we’re still debating why it was built.

Places like this remind us that even with new tech, huge chapters of Earth’s story are still waiting to be deciphered.

#7

Pimburattewa Tank in Sri Lanka is a stunning testament to ancient engineering, crafted by King Parakramabahu I in the 12th century. This magnificent reservoir was ingeniously designed for water storage and irrigation, showcasing the advanced hydraulic systems that early Sri Lankan civilizations mastered. The tank not only reflects the ingenuity of its creators but also their ability to sustain agriculture in a challenging environment. Today, it stands as a remarkable symbol of historical ingenuity, blending functionality with the artistry of ancient infrastructure. The legacy of such innovation continues to inspire and educate those who visit this extraordinary site.

© Photo: Revealed

#8

Castellfollit de la Roca, a gem steeped in history from the 10th century, is no ordinary village. Perched perilously on a 164-foot-high basalt cliff, shaped by the fury of ancient volcanic eruptions, it stands as a testament to mankind’s relentless spirit against nature. This medieval fortress wasn’t just a pretty picture; it was a tactical powerhouse during fierce regional conflicts. As you wander through its narrow, labyrinthine streets and gaze at the sturdy stone houses that have weathered the tests of time, you can’t help but feel the pulse of its rich heritage. The striking 13th-century Church of Sant Salvador isn’t just an architectural marvel; it’s a sign of endurance and resilience. It’s no wonder that adventurous souls flock to Castellfollit de la Roca, lured by its awe-inspiring vistas and the raw, untamed beauty of its surroundings. This isn’t just a destination; it’s a thrilling experience waiting to be unraveled.

© Photo: Antiqua

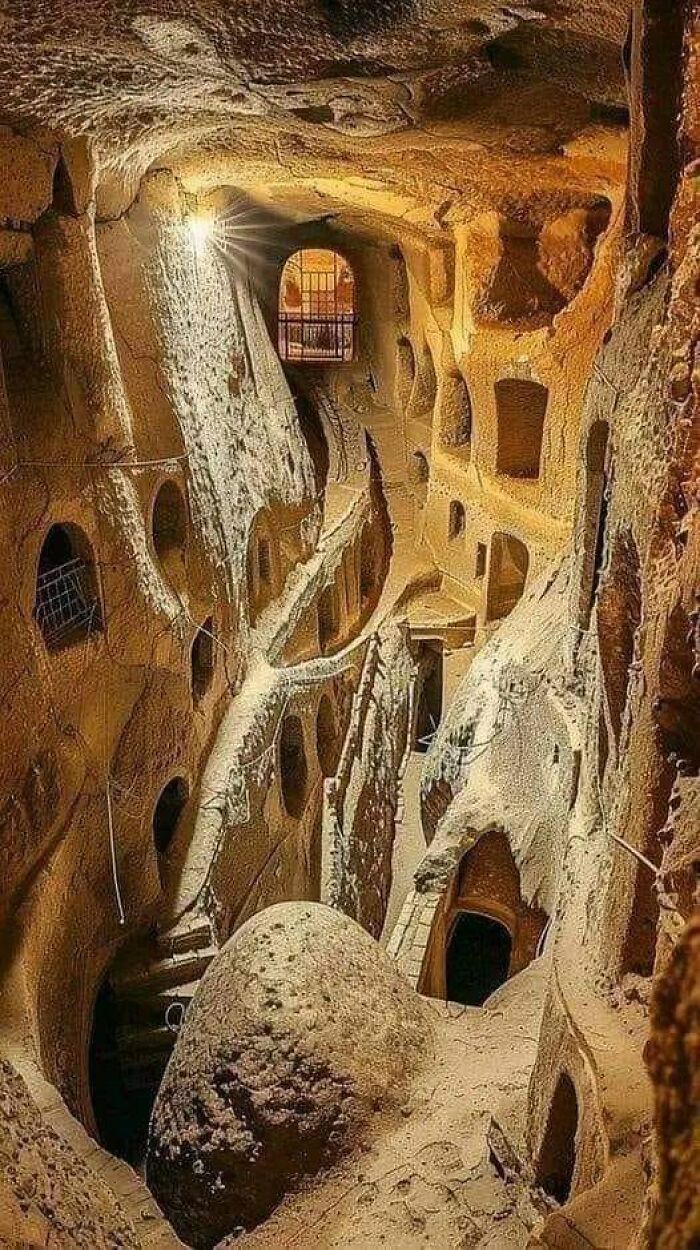

#9

Derinkuyu is a huge underground city in Türkiye

It’s a place where 20,000 people lived! It is nearly 3,000 years old and was found by accident when someone broke a wall in his basement.

Archaeologists have found that it goes down 18 stories and has everything people need to live underground, such as schools, churches and stables

© Photo: Pierangelo Piacentini

Broken tools, small everyday objects, and even ancient trash can often be far more revealing than jewels.

These items show how people cooked, worked, traveled and survived.

For ancient societies with no written records, these objects are often the only stories they left behind.

For example, there are no instruction manuals, no ancient texts for the Stonehenge — just the stones themselves and how the site evolved over time.

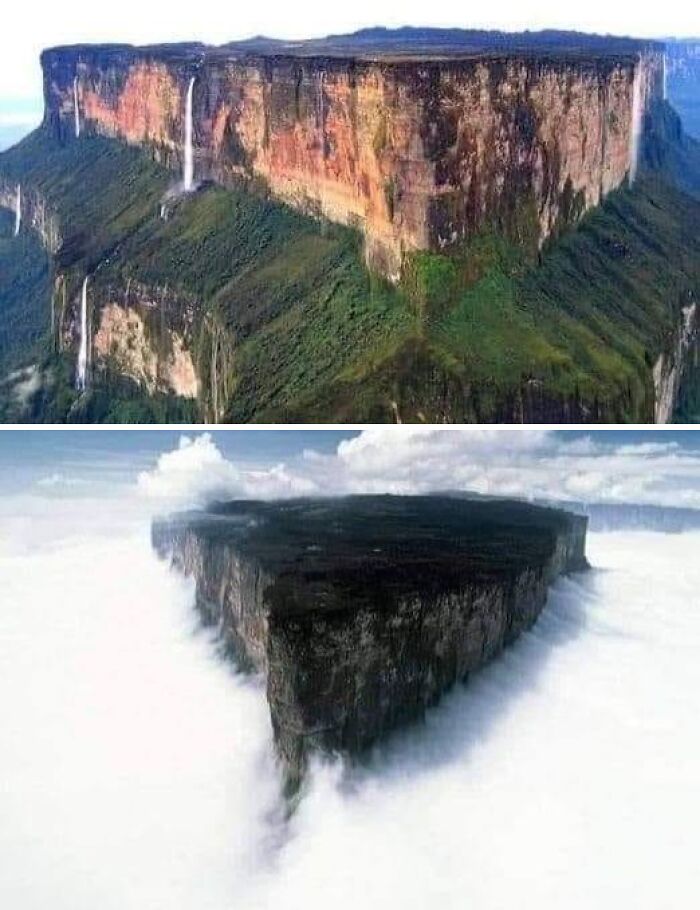

#10

The oldest place on planet Earth is in Venezuela and is called Monte Roraima, Venezuela.

One of the most beautiful and impressive natural wonders in the world.

For more than 500 years, scientists around the world have attempted to decipher the unique geological origin of Mount Roraima, southern Venezuela.

In addition to rising almost 3,000 meters above sea level, the mountain presents an unnatural morphology, which seems to have been cut with knives due to the precision of its million-dollar angles.

This rock formation is the largest of its kind in all of South America and is part of the Pakaraima mountain range. For more than 5 centuries it has intrigued historians, geologists and other scientists because it is a mountain without a point.

The summit of Mount Roraima is completely horizontal and occupies an area of more than 30 square kilometers, surrounded by waterfalls, cliffs and other rare geographical features in the world. Seen this way, it could be considered an island in the hills. Mount Roraima is home to a large variety of endemic animal and plant species.

Geologists and biologists from all over the world estimate that it hides some of the species of which science has no trace, since there are spaces in the mountain that still remain unexplored. Its origin is a mystery. Mount Roraima is thought to have been the product of a major earthquake in the past.

However, its origin is uncertain, as similarly created geological features do not have that shape. This has led scientists to think it may be the oldest rock formation on Earth

© Photo: Pierangelo Piacentini

#11

Hoover Dam.

In the middle of the dam is the Arizona-Nevada border, with a one-hour time difference.

© Photo: Pierangelo Piacentini

#12

The Perito Moreno Glacier is one of the most famous in the world and is located in Los Glaciares National Park, in the province of Santa Cruz, Argentina.

It is part of the Southern Patagonian Ice Field, the third largest freshwater reserve on the planet.

This glacier is known for its impressive size, with a surface area of about 250 km² and a length of about 30 km (18.6 mi). It stands out for its accessibility and for being one of the few glaciers in the world that is not in constant retreat. In fact, it maintains a balance between advance and retreat, making it a geological rarity.

One of its most spectacular attractions is the phenomenon of breakage, when large blocks of ice fall into Lago Argentino, creating an impressive visual and sound spectacle. This phenomenon occurs due to the pressure of the water that builds up behind the glacier, eventually causing the ice barrier that forms to break.

Perito Moreno is one of Argentina’s main tourist attractions, and its beauty and majesty attract visitors from all over the world.

© Photo: Pierangelo Piacentini

One of the many reasons why we’re still discovering new secrets from old finds is because archaeology hasn’t always been done responsibly.

For centuries, tomb robbers and looters stripped various sites just for profit. Even early archaeologists were often tied to colonialism.

Napoleon’s invasion of Egypt famously resulted in tons of artifacts being shipped to France, many of which now fill museum halls like those in the Louvre.

#13

This breathtaking view of Namibia showcases the remarkable convergence of desert and ocean. Towering sand dunes descend sharply into the Atlantic, resulting in a striking and surreal landscape. This unique geographical feature highlights Namibia’s extraordinary natural beauty, where arid land meets the vast sea.

© Photo: Ancient Media

#14

Cave of Crystals – Mexico.

The Crystal Cave is a cave located approximately 300 meters underground in the Naica mine, in the state of Chihuahua, Mexico.

It is famous for its giant selenite crystals, some have a length of up to 11 meters and weigh up to 55 tons.

Dangers of the Crystal Cave: The Crystal Cave is an extremely hostile environment for humans. The temperature inside is 58°C with a humidity of 90-99%, it is therefore impossible to stay more than a few minutes without special equipment.

© Photo: Pierangelo Piacentini

But over time, things have changed drastically. Archaeology has become more scientific and more collaborative — many archaeologists work alongside historians, linguists, and scientists.

Research shows that archaeologists are also working with local and Indigenous groups, making research more inclusive and less extractive than in the colonial past.

“Some of the deepest insights come from people without formal academic credentials. For me, that is the future of archaeology, and of many disciplines: a form of convergence that moves beyond the ivory tower and becomes a collaborative, community-engaged science,” says Ora Marek-Martinez, an archaeologist from the Navajo Native American community.

In most countries, artifacts now legally belong to the place where they’re found, helping preserve cultural heritage where it matters most.

#15

One of the terracotta warriors was found almost perfectly preserved, with detailed footwear designed for grip, showing that people were thinking about practical shoe design over 2,200 years ago.

Each of the 8,000 clay warriors is unique, with no two exactly alike. After the tomb was finished around 210-209 BC, it was robbed and set on fire, causing the roof to collapse and destroying the warriors.

All of the warriors on display today have been carefully restored. These figures were originally brightly painted, but the colors quickly faded until they were discovered in the 1970s.

The warriors were created to guard the tomb of Qin Shi Huang, the first emperor of a unified China. The tomb, which remains locked, is said to contain a replica of his empire, complete with a pearl-decorated ceiling resembling the night sky, rare treasures, and traps to deter thieves.

The workers who built the tomb were buried with the emperor to keep its location secret. Ancient records claim the tomb includes a model of a river

© Photo: Pierangelo Piacentini

#16

La Danta, one of the largest pyramids globally, is a remarkable structure located in the heart of the Guatemalan jungle.

Constructed by the Maya civilization around 300 BCE, this immense pyramid was uncovered in 1926. It reaches an impressive height of approximately 236 feet (72 meters) and encompasses a substantial volume of about 2,800,000 cubic feet (79,000 cubic meters).

The grandeur of La Danta, along with its rich historical significance, continues to captivate the attention of archaeologists and historians. This prompts a compelling question: how many other ancient wonders may still lie concealed within the dense jungle, awaiting their discovery?

© Photo: Pierangelo Piacentini

#17

The Heidelberg barrel is the largest wine barrel in the world, stored in the cellars of the castle of the same name.

It is made of high-quality oak by the famous German craftsman M. Werner.

Its capacity is 212,422 liters.

© Photo: Lulyta Hestiyarti

Cutting‑edge tools like drones, satellite imaging, DNA analysis, and AI are letting archaeologists peer beneath jungle canopies, map lost cities, and even read previously unreadable scrolls.

These technologies are doing more than just speeding up discoveries — they’re making archaeology more precise and less destructive.

#18

City Palace, Jaipur.. India — Blue Room / Chandra Mahal interiors

This cobalt-and-white floral work is part of the City Palace complex (the royal residence), where the palace rooms are famously finished with intricate painted and inlay-style motifs.

© Photo: Nibedita Das

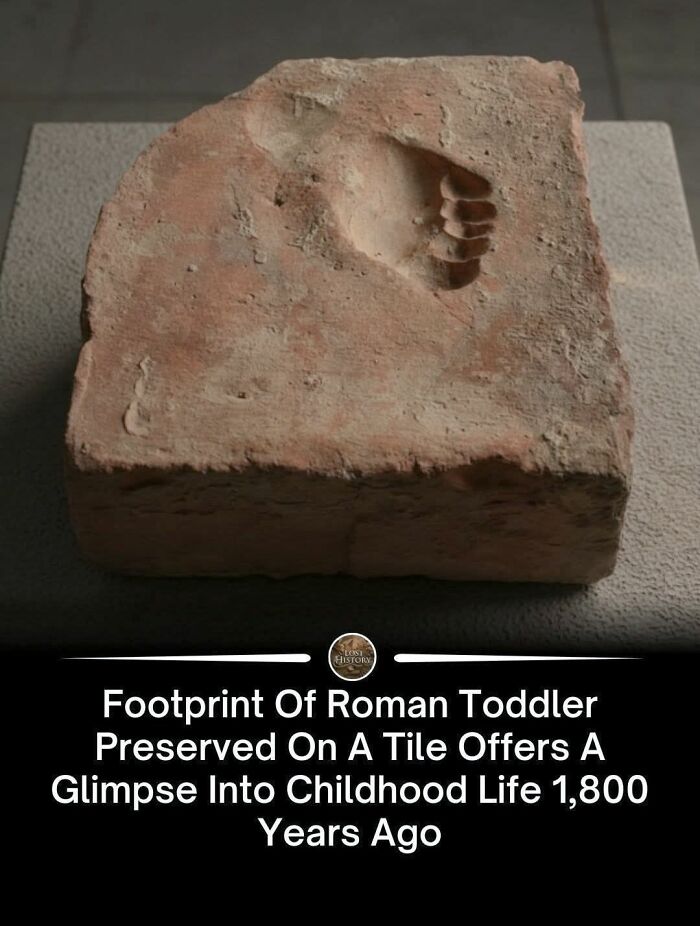

#19

Roman toddler’s footprint has been preserved on a tile for 1,800 years, capturing a fleeting moment from a world long gone. This small impression offers a remarkable connection across time, allowing us to witness a child’s presence in the daily life of ancient Rome.

Archaeologists studying the tile note the clarity and detail of the footprint. Tiny toes, the curve of the heel, and subtle pressure marks reveal the movement and weight of a child. Such traces are rare, as ephemeral moments like these were seldom preserved in the archaeological record, making this find extraordinary.

The footprint also hints at the context of Roman domestic life. Tiles like this were part of homes, workshops, or public spaces, and the impression suggests children moved freely among the adults, leaving traces that would unknowingly endure for nearly two millennia. Each mark invites curiosity about the child’s day, the environment, and the family that lived around them.

Beyond the scientific perspective, the footprint sparks wonder. It reminds modern observers that even small, everyday actions, running, playing, or stepping on wet clay, can leave a lasting record. History sometimes speaks through the tiniest of details, preserving stories of life, growth, and human presence.

This Roman footprint connects us to childhood, play, and the ordinary moments of ancient life, showing that the past is full of tiny mysteries waiting to be recognized and remembered.

© Photo: Lina Wijayanti

#20

Archaeologists have uncovered a rare carved Pictish stone near the village of Aberlemno in eastern Scotland, dating to the 5th or 6th century A.D.

The Picts are famous for leaving behind mysterious symbol stones, but each new discovery is important because so much about their culture remains unknown. These stones were likely used as markers of identity, territory, or commemoration, and their symbols may have carried social, political, or even religious meaning.

The Aberlemno area is already known for its impressive Pictish monuments, and this new find adds another piece to the puzzle of how these early medieval people expressed power and belief. Finds like this help historians better understand a society that left no written records of its own, yet clearly possessed a rich visual language and a strong sense of identity carved into stone.

© Photo: Lina Wijayanti

Natural wonders and amazing feats of engineering are just as incredible and unbelievable as prehistoric objects.

An underground city hidden beneath Türkiye, the Passage du Gois in France that disappears under the sea twice a day, or the incredible terraces of Machu Picchu — each one a little puzzle the world has left for us.

We’re still uncovering parts of the world we didn’t even know existed, and who knows what’s waiting to be discovered around the next corner?

#21

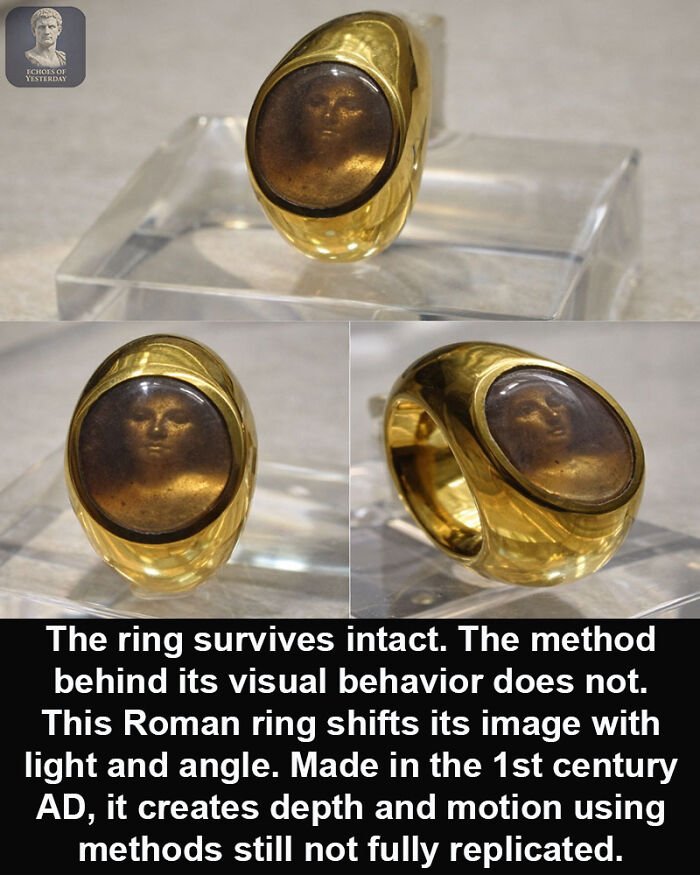

Roman jewelry is not supposed to do this. This ring was found in the burial site of Ebutia Quarta, a Roman noblewoman who lived in the 1st century AD. At first glance, it appears to be a gold ring set with a dark gemstone. When viewed from different angles, the image within shifts, gaining depth and clarity instead of flattening.

The effect resembles a controlled optical illusion, produced without lenses, electronics, or modern polishing tools. Roman artisans were skilled, but this level of visual manipulation is rarely associated with personal jewelry from the period.

The subject, location, and date are well documented. The craftsmanship is real. What remains unclear is how consistently such effects could be produced and whether this was an isolated achievement or part of a broader, now-lost technique.

© Photo: Remember When

#22

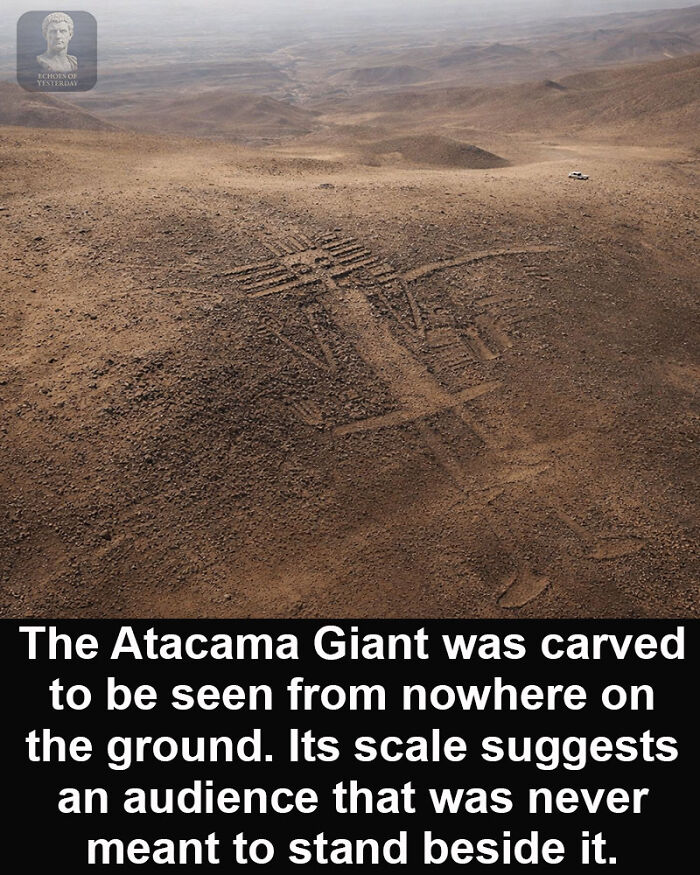

The Atacama Giant immediately breaks a basic expectation of ancient art. It was not made to be viewed up close. Carved into the Cerro Unitas hillside in Chile between 1000 and 1400 AD, the geoglyph reaches over 115 meters in length and only resolves into form from high above the desert.

The figure depicts a humanoid shape with linear markings across its body and head, details thought to relate to astronomy, seasonal cycles, or ritual symbolism. Archaeologists link it to indigenous cultures of the Atacama region, who lived in one of the driest environments on Earth and relied heavily on celestial knowledge for survival.

No structures exist from which the full figure could be observed during its creation. There are no inscriptions explaining its purpose. Some researchers see it as a calendar tied to lunar or solar events. Others note that its scale exceeds practical necessity. What remains certain is that it was designed with distance in mind, leaving open the question of who, or what, that distance was meant to serve.

© Photo: Echoes of Yesterday

#23

A 1,600-year-old skull with a golden patch—this remarkable artifact at the Museum of Gold in Lima is proof of the Inca’s daring surgical skill. The practice of trepanning, where the skull was opened to relieve trauma or illness, was already bold. But using gold to cover the wound? That elevates it to another level. Even more astounding: the patient survived, as the healed bone reveals. This isn’t just a relic—it’s a gleaming symbol of medical innovation, craftsmanship, and resilience from a civilization far ahead of its time.

© Photo: GoodScience

#24

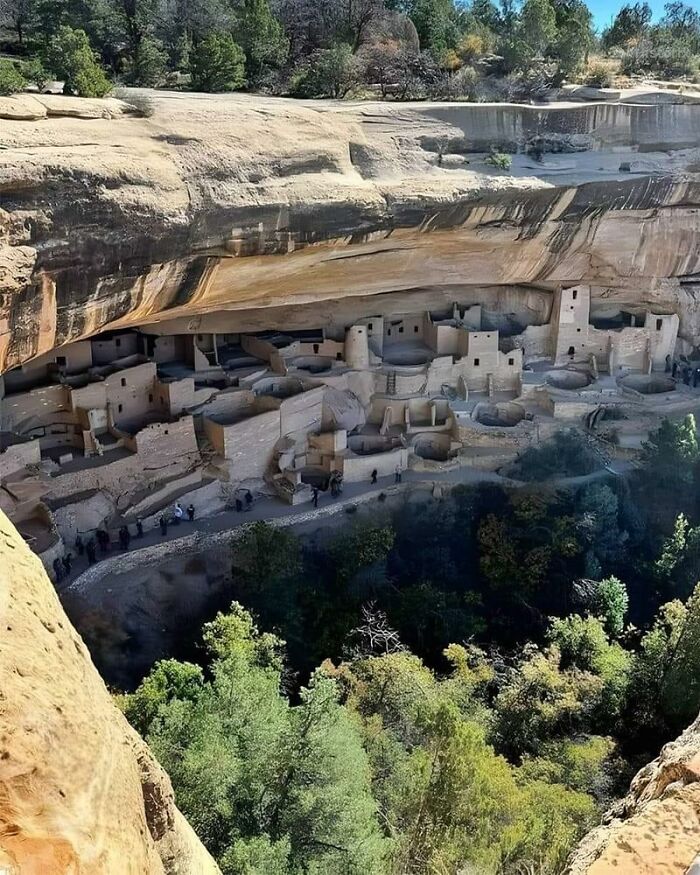

Step into a world of ancient wonder at Cliff Palace in Mesa Verde National Park, Colorado, the largest cliff dwelling in North America. Constructed by the Ancestral Puebloans between 1190 and 1260 CE, this remarkable site features 150 rooms and 23 kivas, each showcasing the remarkable architecture of a sophisticated civilization. Nestled into the cliffs for protection and strategic advantage, the intricate masonry tells a story of creativity and resilience. Visiting this awe-inspiring location offers a glimpse into the rich history and culture of the people who called this extraordinary place home.

© Photo: Historix

#25

Imagine a statue that once soared 157 feet into the sky, a colossal tribute to the sun god Helios, casting its shadow over Rhodes. Erected between 292 and 280 BCE by the skilled sculptor Chares, the Colossus of Rhodes celebrated the island’s triumph over Cyprus. Crafted from iron and brass and filled with stone, this marvel stood proudly at Mandraki Harbor for 54 remarkable years. However, tragedy struck in 226 BCE when a powerful earthquake shattered its grandeur, leaving only mystery in its wake. Today, the Colossus continues to captivate our imagination through artistic representations of its former glory.

© Photo: Ancientra

#26

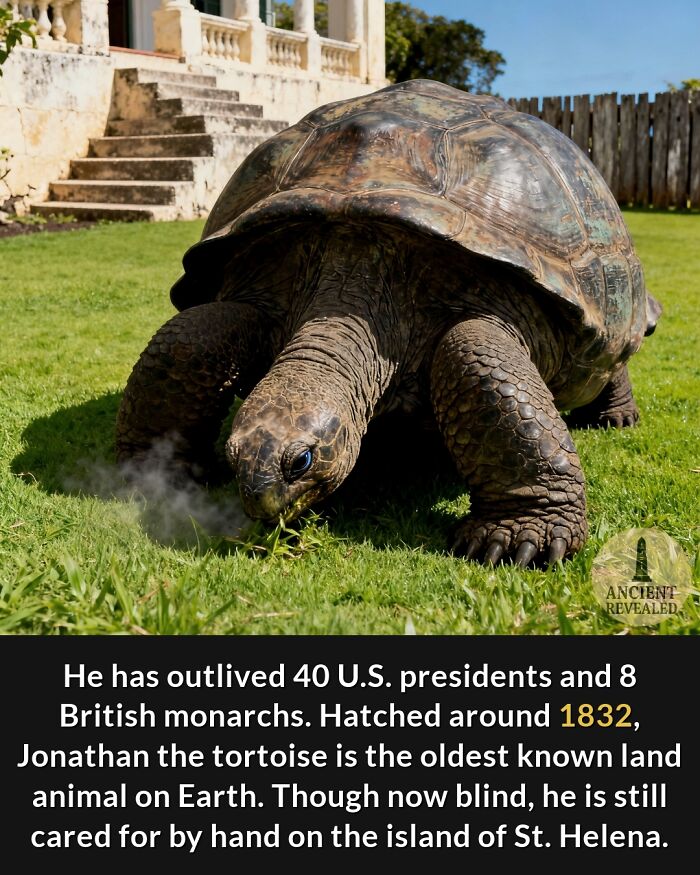

Born before the lightbulb was invented, Jonathan the tortoise is a living piece of history. At an estimated 192 years old, he is the oldest known land animal on Earth and has lived through nearly two centuries of incredible change.

© Photo: Ancient Revealed

#27

In the arid expanse of Wadi Al Hitan, an Egyptian desert region, a 37-million-year-old whale skeleton has been uncovered, adding to a significant collection of ancient marine fossils. This site, known as the Valley of the Whales, has revealed dozens of rare fossilized whale skeletons, offering invaluable insights into prehistoric marine life.

To safeguard these remarkable discoveries and promote their study, a dedicated museum has been established at the site. This museum not only helps preserve the fossils but also serves as an educational hub, shedding light on the evolutionary history of whales and the ancient environments they inhabited.

© Photo: Nibedita Das

#28

It’s the longest bridge in the United States, spanning 23.79 miles across Lake Pontchartrain.

It’s also the longest continuous bridge over water in the world.

The bridge connects New Orleans with smaller communities on the north shore of the lake.

It’s made up of two parallel bridges supported by 9,500 concrete pilings.

And do NOT get on this road with a rickety car! Also, have enough gas to drive for at least another 45 minutes and a good spare tire before you DO..

© Photo: Tia Chayankdia

#29

The economy section of a Pan Am 747 in the 1970s.

© Photo: Lina Wijayanti

#30

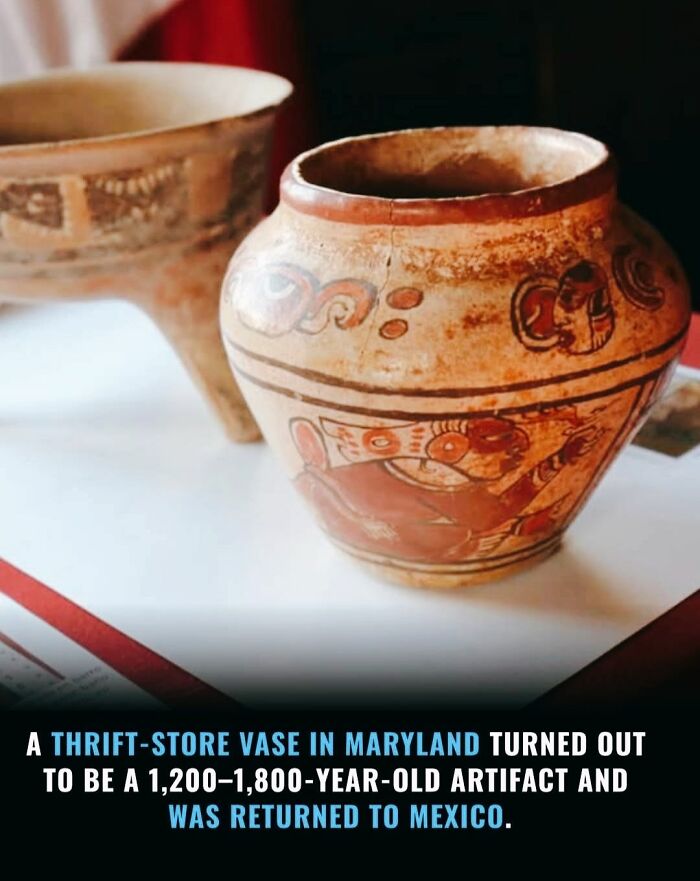

A remarkable story of chance and responsibility unfolded when a woman who had bought a ceramic vase at a Maryland thrift store about five years ago learned that it was no ordinary decoration.

Experts determined the vessel was likely made between A.D. 200 and 800, placing it firmly in the ancient past of Mesoamerica. Realizing the object’s true cultural and historical significance, she chose to return it rather than keep or sell it. The vase was officially repatriated to Mexico during a ceremony in Washington, D.C., marking the end of its unexpected journey through modern hands.

Such returns are vital for preserving cultural heritage, allowing artifacts to be studied, protected, and appreciated in their proper historical context. The episode shows how even everyday places like thrift stores can occasionally hold pieces of deep history and how individual choices can help repair the past.

© Photo: Lina Wijayanti

#31

New France was failing for a simple reason. Too many men. Too few women. In 1663, King Louis XIV intervened directly in the struggling colony of New France, centered in present-day Quebec. Over the next decade, around 800 women, later known as the Filles du Roi, were sent from France.

Most were young, from modest, homeless or orphaned backgrounds, and each received a royal dowry to ensure marriage and permanence.

Their role was precise. They chose husbands from among settlers, married quickly, and began families almost immediately. Within a decade, the colony’s population doubled. Farms stabilized. Communities stopped dissolving. Birth rates surged.

One detail stands out. These women were not forced into matches. Choice was central to the plan, an unusual policy for the seventeenth century.

The records document the outcome clearly. Modern genealogical studies show that most French Canadians today descend from at least one Fille du Roi.

The strategy worked. What remains open is whether New France survived because of royal planning, or because these women chose to stay and build lives in a place that had little reason to keep them.

© Photo: Echoes of Yesterday

#32

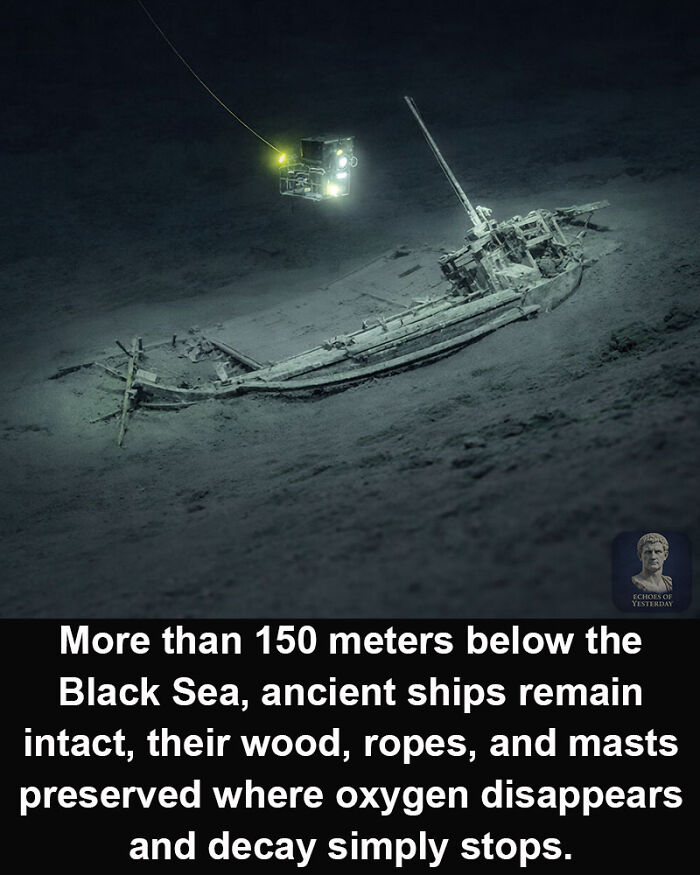

The ships look newly sunk. Their age says otherwise. In the Black Sea, beneath 150 meters of water, dozens of ancient shipwrecks rest in near-perfect condition. Discovered by the Black Sea Maritime Archaeology Project, these vessels span Greek, Roman, Byzantine, and Ottoman periods.

One Greek trading ship dated to around 400 BC still preserves its mast, steering oar, benches, and hull structure.

The key detail is not craftsmanship alone. It is chemistry. Below a certain depth, the Black Sea becomes anoxic, completely lacking oxygen. In this zone, wood-boring organisms cannot survive, and decay stops almost entirely.

Historians recognize the dates, ship types, and trade routes these wrecks represent. What remains uncertain is how much maritime history elsewhere has been permanently lost without such conditions. Here, preservation rewrites expectations, revealing how fragile our archaeological record truly is.

© Photo: Nouza Expla

#33

The lake looks calm, but the lakebed tells a different story. In Lake Kootenay, Canada, aerial imagery has revealed a submerged circular geoglyph carved into the sediment below. The pattern consists of a central ring with straight linear features extending outward, visible only under specific light and water conditions.

Natural processes can shape landscapes in unexpected ways, but the symmetry here draws attention.

One concrete detail stands out. The lines appear cut into the lakebed rather than formed by currents, which typically leave irregular traces. This raises the possibility of human modification before the area was flooded or before water levels rose to their current state.

No archaeological consensus exists. The feature has not been formally dated, and no associated artifacts have been documented. It may reflect an ancient marker, a later construction now submerged, or a coincidence amplified by perspective.

The geoglyph remains underwater, unexcavated and largely unstudied. Whether it represents intentional design or an unusual convergence of natural forces, the lake preserves the pattern without explanation, waiting for closer examination rather than quick conclusions.

© Photo: Remember When

#34

Swords in the Rock – Where a Kingdom Was Born

On the shores of the fjord near Stavanger, three enormous Viking swords stand firmly embedded in stone, gazing over Norway’s cold waters. Known as Sverd i fjell (“Swords in Rock”), the monument commemorates the legendary Battle of Hafrsfjord — the event that paved the way for the unification of Norway under King Harald Fairhair.

The central sword symbolizes victory and authority, while the two smaller swords represent the defeated rulers. Yet the monument carries a deeper meaning: once planted in solid rock, the swords can never be lifted again — a powerful reminder that peace is meant to last.

A place where history, legend, and the dramatic Nordic landscape merge into one unforgettable scene.

© Photo: Ceausu Gabriel

#35

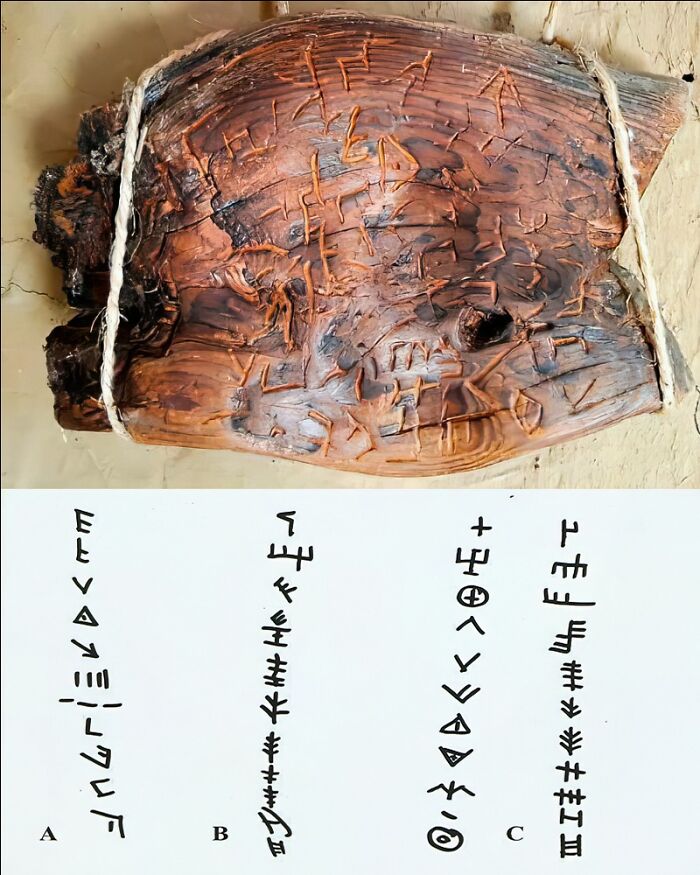

Long before the rise of Sumer and the advent of cuneiform, there existed Dispilio. Unearthed in 1993 in northern Greece, this ancient wooden tablet, estimated to be around 7,000 years old, showcases a form of writing that predates the Mesopotamian script by more than a thousand years. Discovered at a Neolithic settlement by the lakeshore, its enigmatic engravings have yet to be fully deciphered, sparking debate among scholars. Could it serve as a method of record-keeping or represent an early form of alphabet? Regardless of its purpose, this artifact challenges conventional timelines of written language and suggests that the development of symbolic communication might have occurred independently across various regions of prehistoric Europe.

© Photo: Vlad Diaconu

#36

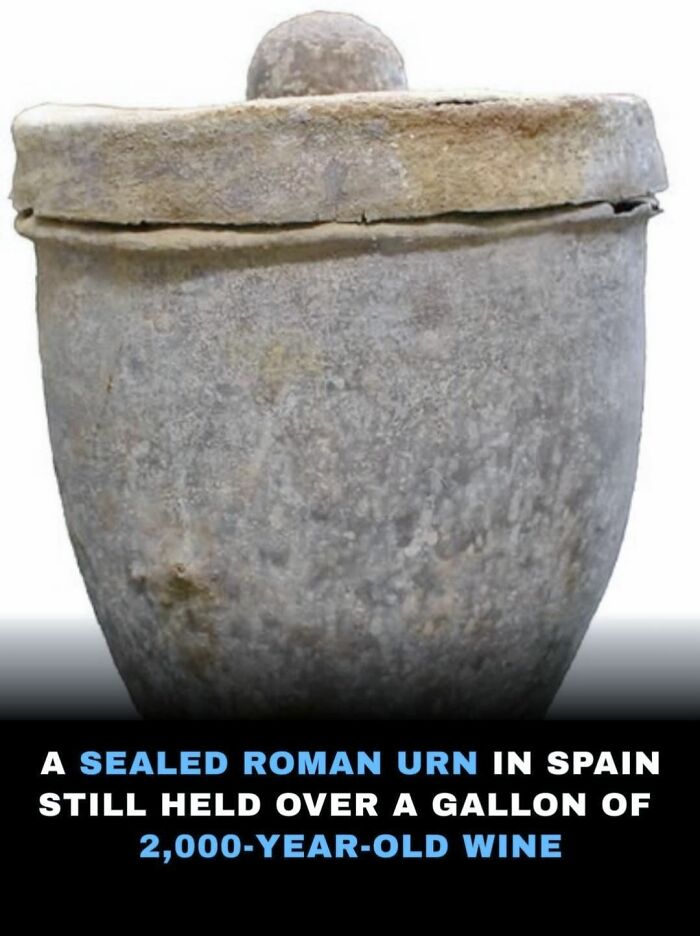

When archaeologists opened a 2,000-year-old glass burial urn found in a mausoleum in the ancient Roman city of Carmo in southwestern Spain, they expected dust or residue. Instead, they were stunned to discover it still filled with more than a gallon of liquid.

Laboratory analysis revealed the impossible-sounding truth: it was ancient Roman wine, preserved for two millennia inside the sealed container. The urn had been placed in a tomb as part of a cremation burial, likely as an offering to honor the dead in the afterlife. Its airtight seal and stable conditions allowed the liquid to survive when it should have long since vanished.

This extraordinary find is now considered the oldest known liquid wine ever discovered, offering a rare, tangible taste—at least in theory—of the Roman world.

© Photo: Lina Wijayanti

#37

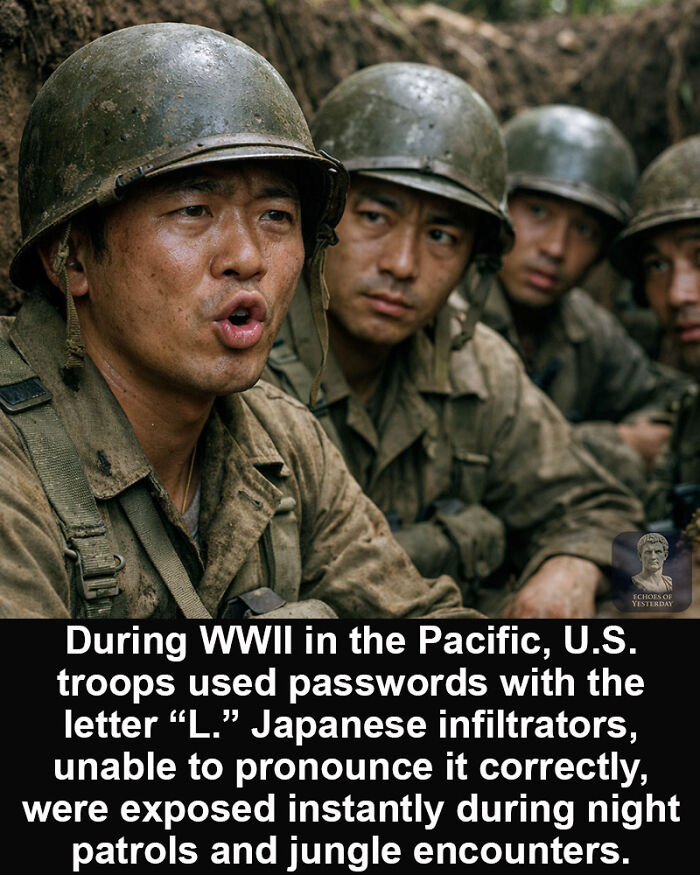

The Pacific War was fought in darkness, humidity, and constant fear. During World War II, U.S. troops operating in jungle terrain faced a specific threat: Japanese soldiers infiltrating lines while posing as American or allied forces. Visibility was poor, encounters were sudden, and hesitation could be fatal.

To counter this, American units adopted a linguistic test. Passwords were chosen specifically because they contained the letter “L,” a sound that does not exist in the Japanese language in the same form. Words like “lollapalooza” or “lightning” became tools of identification. A reply that shifted “L” into “R” was treated as immediate proof of infiltration.

This method, later known informally as the “L test,” reflects the brutal logic of close-range jungle warfare. Decisions were made in seconds, with no margin for correction.

Language became a weapon.

© Photo: Echoes of Yesterday

#38

This looks like wood. It isn’t. In Petrified Forest National Park, Arizona, fallen trees from the Late Triassic Period, around 220 million years ago, remain scattered across the landscape. What appears to be grain, bark, and growth rings is actually stone.

The transformation is precise. After burial, groundwater rich in silica moved through the logs. Organic material decayed, but its microscopic structure remained. Over time, silica crystallized in place, replacing each cell with quartz while preserving the original form. The result is wood in shape only, gemstone in substance.

One detail stands out when viewed closely: growth rings and knots are still visible, yet they fracture like glass. Color bands come from trace minerals, iron, manganese, and carbon, locked in during crystallization.

Geology explains the process. What it cannot fully recreate is the scale. Entire forests fossilized where they stood.

The trees are mapped. The chemistry is known. What remains uncertain is how often landscapes like this vanish so completely, leaving only stone memories behind.

© Photo: The Nostalgic Era

#39

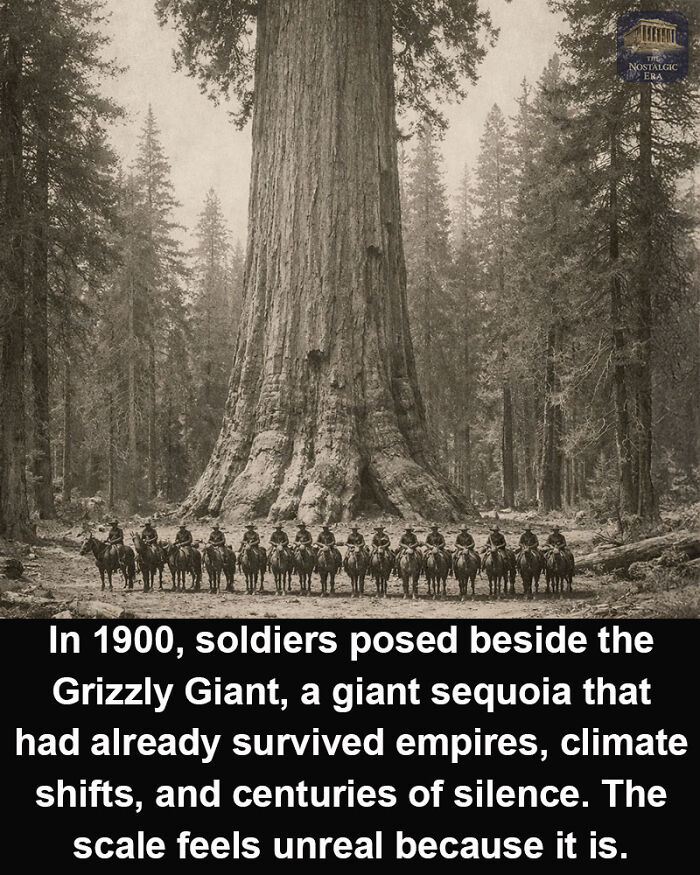

The people look temporary. The tree does not. This photograph shows U.S. cavalry soldiers gathered at the base of the Grizzly Giant, located in Mariposa Grove, California. When the image was taken around 1900, the tree was already estimated to be nearly 3,000 years old, meaning it began growing long before classical civilizations emerged.

One detail stands out immediately: the trunk width. Even a mounted line of soldiers barely spans a fraction of its base. This sequoia grew without haste, adding only millimeters per year, yet accumulated mass that modern engineering still struggles to rival.

Scientists agree on its age range and species. They also agree that trees like this are rare survivors. What remains less clear is how many such giants once existed before logging and settlement erased them from the landscape.

The photograph documents the moment. The scale documents something else entirely.

© Photo: The Nostalgic Era

#40

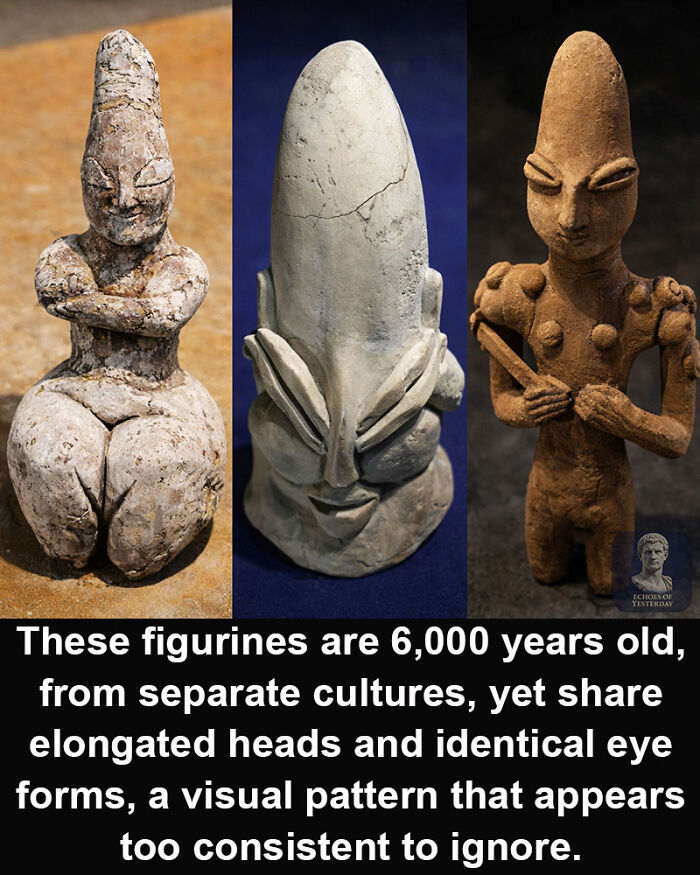

The similarity is the first thing you notice. These 6,000-year-old figurines, discovered in separate regions and cultures, were not produced in isolation of time, yet they share the same visual language. Elongated skulls, sharply defined eyes, and upright, rigid postures appear again and again, carved by hands that never met.

The cultures differ. The materials differ. The geography does not overlap. Yet the forms persist.

One concrete detail stands out: the skull shape. It is exaggerated in all three figures, not as decoration, but as the defining feature. This is not a minor artistic flourish. It dominates the design.

Archaeology offers several possibilities, symbolic tradition, ritual stylization, or shared human practices such as cranial modification. None fully account for the precision or consistency across distance.

What these figures represent is still debated. They document something real to the people who carved them. Whether memory, belief, or observation, the repetition itself remains the unanswered detail that keeps drawing attention back to the stone.

© Photo: Echoes of Yesterday

#41

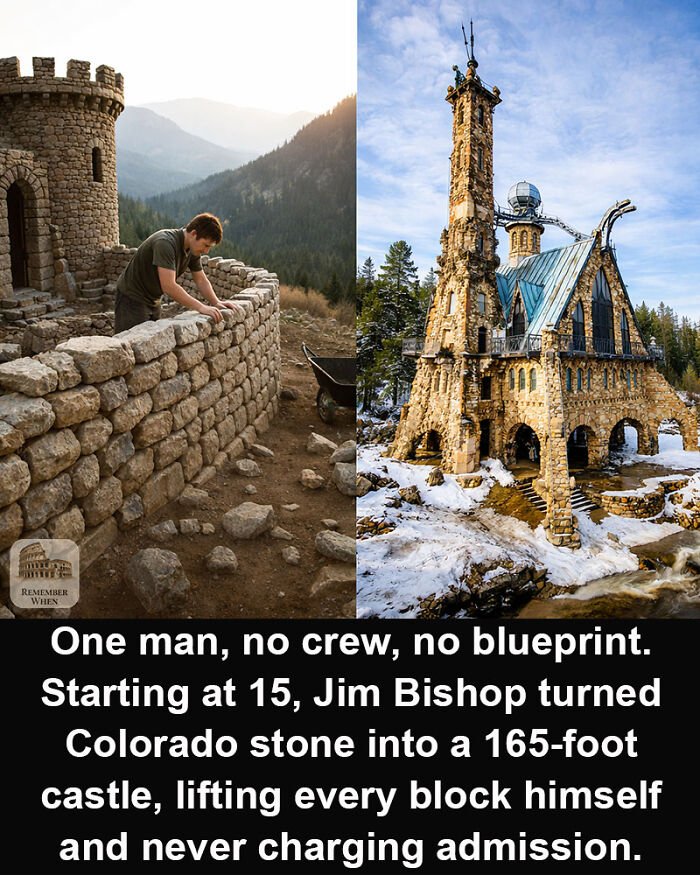

This structure was never supposed to exist. In the mountains of central Colorado, Jim Bishop began building what he said would be a small stone cabin after buying land in the 1950s for $450. The project never stopped. Decade after decade, working alone, he turned that idea into Bishop Castle, now rising roughly 165 feet above the trees.

There were no architects, no contractors, no formal plans. Bishop quarried stone by hand, welded his own ironwork, and lifted materials using homemade pulleys and scaffolding. One visible detail anchors the scale: a narrow spiral staircase climbing inside a single tower, set entirely by hand-laid stone.

Today the castle includes stained glass, iron bridges, ballrooms, and sculpted dragons. It remains unfinished by design. Bishop still works on it, and he has never charged admission.

The method is known. The timeline is documented. What lingers is not how it was built, but why someone chose to spend a lifetime proving it could be

© Photo: Remember When

#42

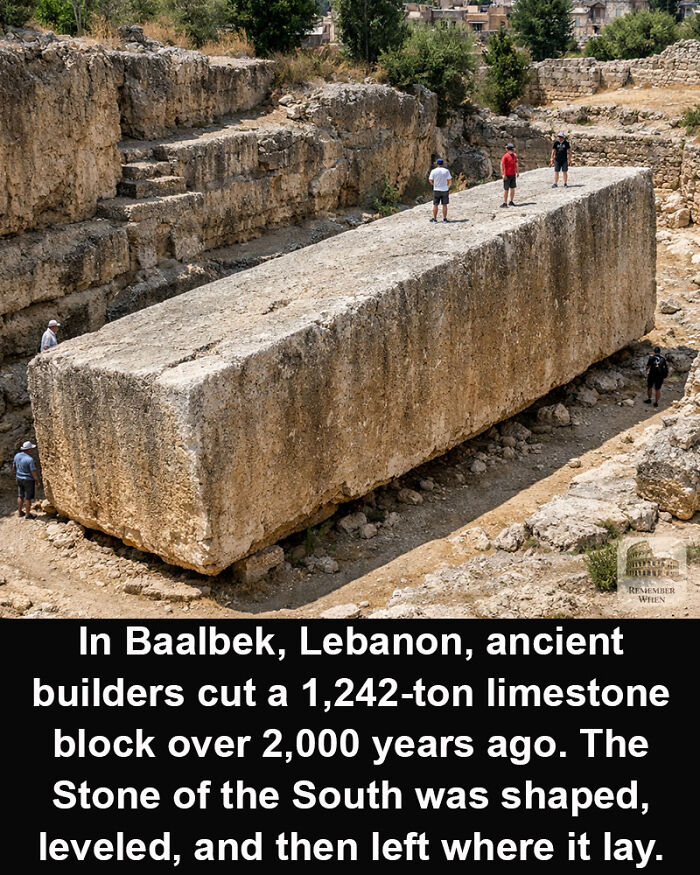

The stone is finished, but it never arrived. Imagine carving a stone heavier than most modern structures allow, then leaving it half-freed in a quarry. The Stone of the South, unearthed in the 1990s at Baalbek, Lebanon, dates back over 2,000 years and embodies that exact contradiction: a 68-foot-long monolith weighing 1,242 tons (2,484,000 pounds), shaped with precision that defies the era’s known capabilities.

One standout detail is the clean, vertical cut separating it from the surrounding bedrock—evidence of systematic quarrying where workers removed layers inch by inch, creating a trench deep enough for extraction. No machinery existed then, only chisels, hammers, and perhaps wooden levers or rollers.

Explanations fall short; while some suggest ramps and manpower, replicas at this scale consistently fail to match the original’s accuracy without industrial aid. Lost techniques, like specialized leverage systems, remain possible but unproven.

The stone never moved from its spot. It waits in the quarry still. What halted the ancients mid-task, and what forgotten skill made the attempt possible at all?

© Photo: Remember When

#43

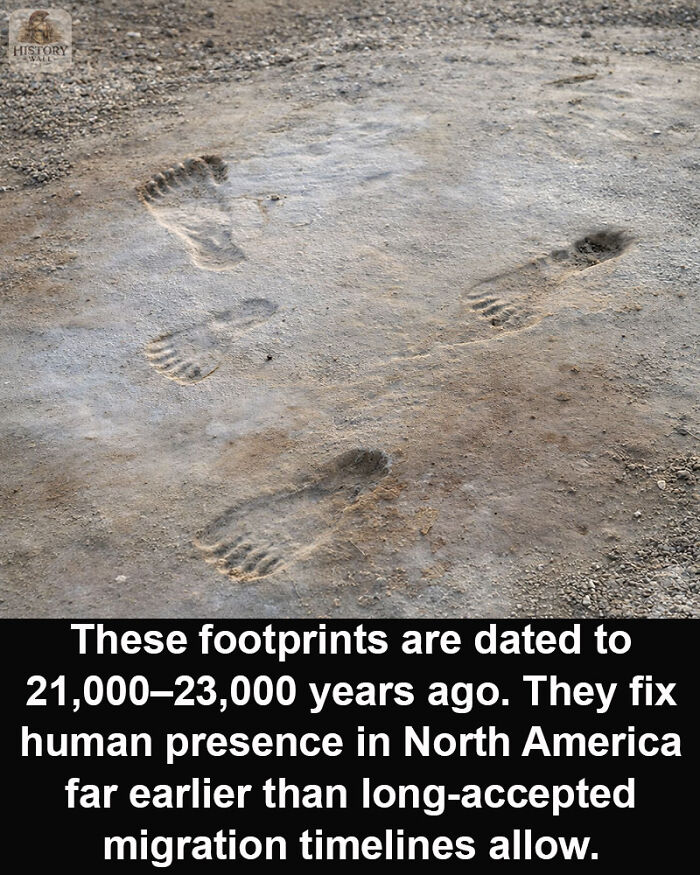

The evidence appears small. The consequence is not. In 2021, researchers confirmed that fossilized human footprints found at White Sands National Park date to between 21,000 and 23,000 years ago. Preserved in ancient lakebed sediments, the prints were securely dated using plant material trapped within the same layers.

One detail shifts the narrative immediately. The majority of the 61 footprints were made by children and adolescents. This was not a brief hunting party or exploratory edge. It reflects repeated, everyday movement by a living community during the height of the last Ice Age.

For decades, dominant models placed the first humans in North America around 13,000 years ago. These footprints push that presence back by roughly 10,000 years, forcing migration routes, timing, and survival strategies to be reconsidered.

No structures were left behind. No tools announce their arrival. Yet the ground itself records what theory resisted. People were there, long before the timeline was ready to include them.

© Photo: Nouza Expla

#44

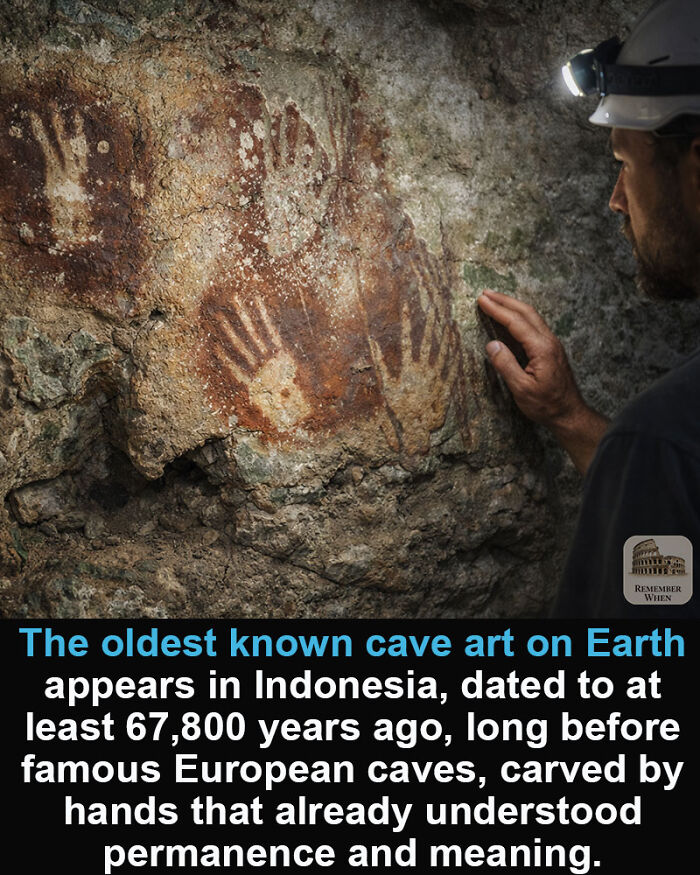

These handprints are older than the story we usually tell about art. In limestone caves on Sulawesi, Indonesia, researchers identified hand stencils dated to at least 67,800 years ago, making them the oldest known cave art on Earth.

The images were created by placing hands against stone and blowing mineral pigment around them, leaving sharp outlines that still hold their form.

One detail stands out. Several fingertips were deliberately altered, reshaped to appear pointed, suggesting choice rather than accident. This was not random marking. It followed a method.

The age was determined by dating mineral crusts that formed over the artwork, anchoring the images firmly in deep prehistory. Who made them remains uncertain. They may belong to early Homo sapiens moving through Southeast Asia, or to Denisovans known to have lived in the region.

What is clear is that symbolic behavior existed far earlier, and far wider, than once assumed. The timeline is established. The origin story is still unfolding.

© Photo: Remember When

#45

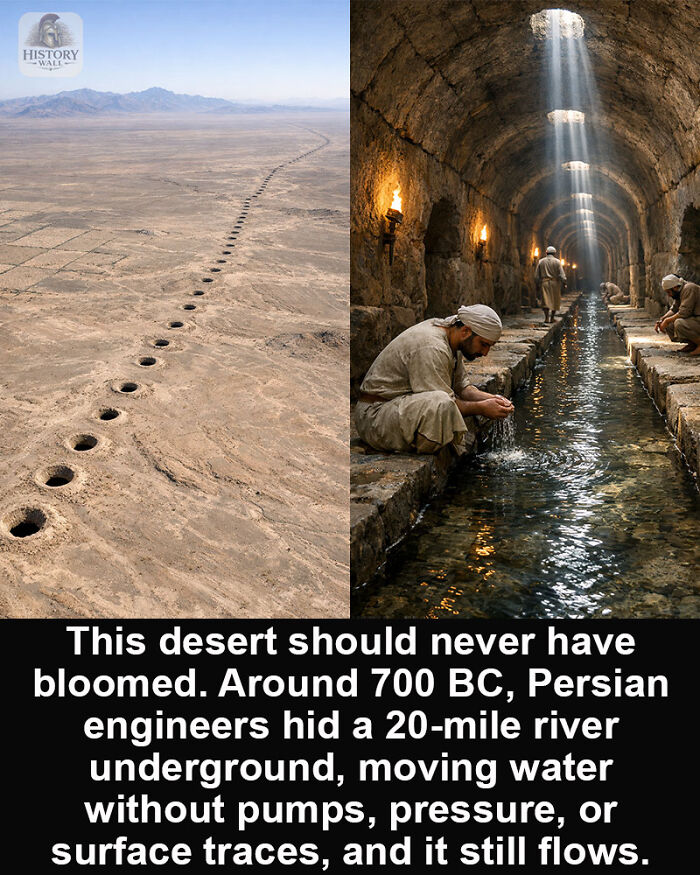

A river built where no river should exist. Around 700 BC, in ancient Persia, engineers constructed what is now called a qanat, a 20-mile subterranean channel carved beneath the desert to carry water from distant aquifers using gravity alone.

Vertical shafts punctured the surface at regular intervals, allowing construction, airflow, and maintenance while keeping the water protected from heat and evaporation. Many of these systems still function more than 2,700 years later. No pumps. No electricity. No visible river.

The full precision of how gradients were maintained across such distances remains limited by surviving evidence, yet the water still arrives, quietly, as it always has.

© Photo: Nouza Expla

#46

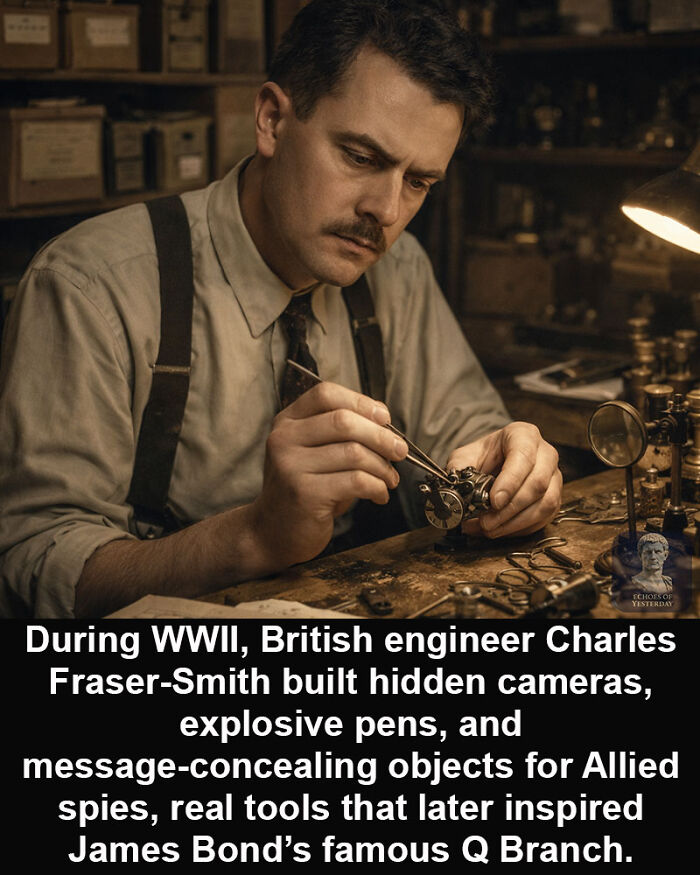

During the Second World War, British intelligence relied not only on codes and informants, but on engineering disguised as ordinary life. At the center of this effort was Charles Fraser-Smith, an inventive mind working with Special Operations Executive and MI6.

His job was simple to describe and dangerous to execute: create tools that allowed agents to survive unnoticed behind enemy lines.

Fraser-Smith produced cameras hidden in buttonholes, pens packed with explosive charges, hollow coins, altered shoes for smuggling documents, and everyday objects converted into weapons or communication devices. Internally, many of these inventions were referred to as “Q devices,” reflecting their classified status and experimental nature.

These gadgets were purely mechanical, designed decades before digital surveillance. Their success depended on precision, reliability, and disguise, not technology alone.

One man took careful note. Ian Fleming, who served in naval intelligence, later transformed Fraser-Smith’s real-world inventions into fiction through the gadget master Q in James Bond.

Behind the cinematic fantasy stood a real engineer, solving life-or-death problems with pens, buttons, and quiet ingenuity.

#47

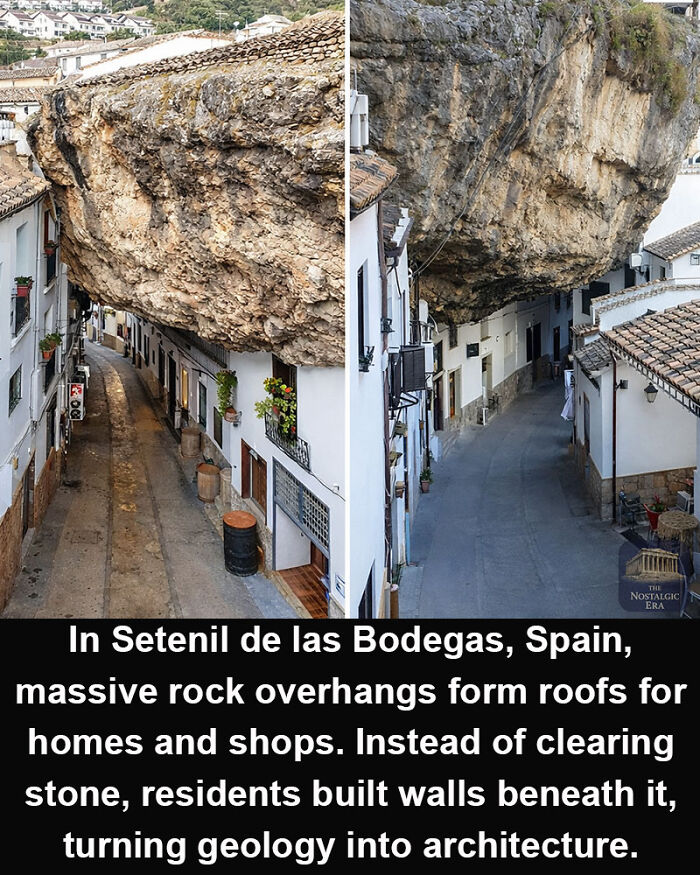

The stone was never removed. It was accepted. Setenil de las Bodegas, located in the province of Cádiz in southern Spain, is defined by its decision to build with the landscape rather than against it. For centuries, residents expanded natural caves along the Río Trejo gorge by adding exterior walls beneath massive rock overhangs, creating streets where stone forms the ceiling.

One specific detail reveals the logic behind this approach. The rock provides natural thermal regulation, keeping interiors cool in summer and warmer in winter, long before modern climate control existed. This practical benefit shaped how the town developed over time.

The settlement traces its roots back to prehistoric habitation, with later Roman and Moorish presence influencing its growth. Yet the exact timeline of when each rock dwelling was adapted remains unevenly documented.

What stands today is not a single architectural project, but a long negotiation between human need and geology. The town persists as evidence that survival and design do not always require domination of nature, only careful accommodation.

#48

Look closer at this path in Calvi dell’Umbria, Italy. What appears as a charming medieval alley is actually a deliberate spiral staircase carved into the hillside, winding through the historic center with no wasted angle. The cobblestones, worn smooth over centuries, lead past rustic doors and balconies clinging to buildings that have stood since at least the Middle Ages, in a settlement whose roots stretch back to the Bronze Age.

The real tension lies in the bronze plaque fixed at the very heart of the spiral’s base. Visible in the photo, it bears an inscription that locals and visitors pass daily, yet its exact purpose, commemorative, dedicatory, or boundary marker, remains undocumented in most accounts of the village.

The pathway itself integrates seamlessly with arches and remnants of old walls, suggesting the entire layout was planned around this curving descent rather than the other way around.

Modern feet still follow the same route daily. The plaque endures untouched. What message did someone embed here, knowing the steps would carry it forward for generations?

#49

© Photo: Echoes of Yesterday

#50

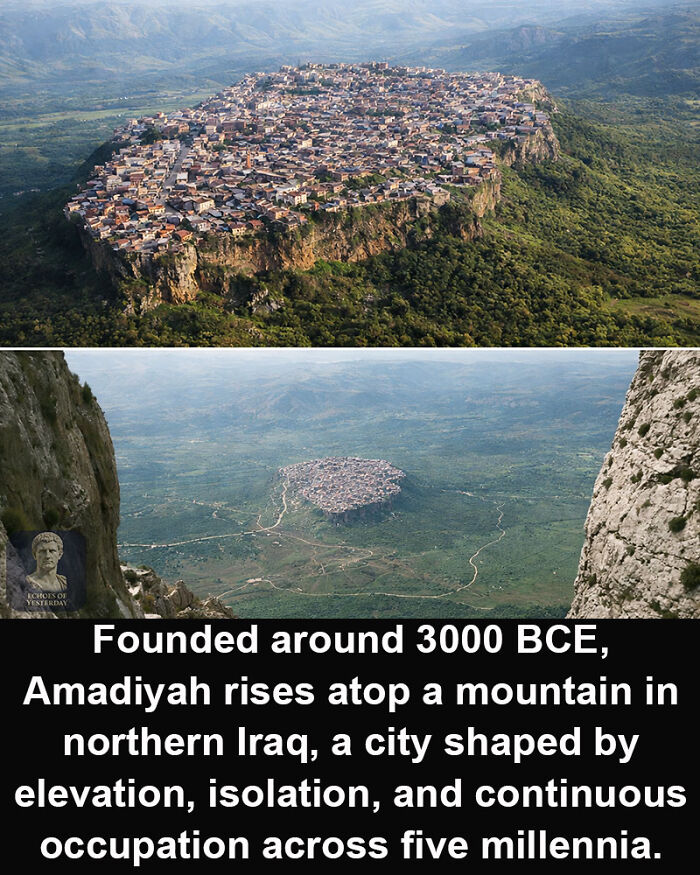

The location explains survival better than legend. Amadiyah, also known as Amedi, sits atop a flat-topped mountain rising sharply above the surrounding valleys. Archaeological and historical sources trace settlement here back to around 3000 BCE, making it one of the oldest continuously inhabited locations in the region.

One detail defines the city immediately. The plateau functions as a natural fortress, with steep cliffs on all sides and limited access points. This geography shaped how Amadiyah endured as empires changed around it, from Assyrian and Median control through later regional powers.

The city’s layout reflects adaptation rather than expansion. Space is finite. Defense is built into the land itself. Unlike cities that grew outward, Amadiyah was forced to refine what already existed.

The date is ancient. The position is unmistakable. What remains difficult to trace is how many layers of its earliest history lie buried beneath later streets, compressed by thousands of years of uninterrupted human presence.

© Photo: Echoes of Yesterday

#51

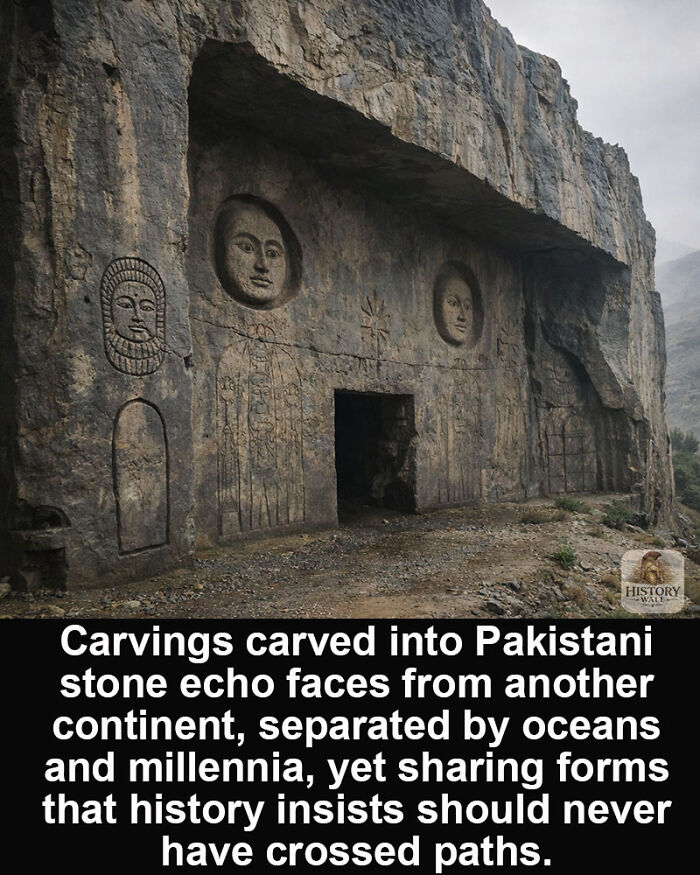

These carvings, found in Pakistan and cut directly into exposed rock, challenge an assumption that ancient cultures developed in isolation. The faces, with heavy features, stylized eyes, and deliberate symmetry, resemble artistic conventions commonly associated with the Olmec civilization of Mesoamerica, active roughly between 1500 and 400 BCE.

Mainstream archaeology places the Olmecs firmly in the Americas, with no verified evidence of transoceanic contact with South Asia. In Pakistan, the carvings are typically interpreted within local religious or cultural traditions, shaped by regional beliefs rather than foreign influence. Yet the visual overlap remains difficult to dismiss at a glance.

No inscriptions link these works, no tools trace a shared origin, and no texts describe contact. The similarity exists only in stone and form, recorded but unexplained. Whether coincidence, parallel development, or something not yet understood, the resemblance lingers without asking permission from established timelines.

© Photo: Nouza Expla

#52

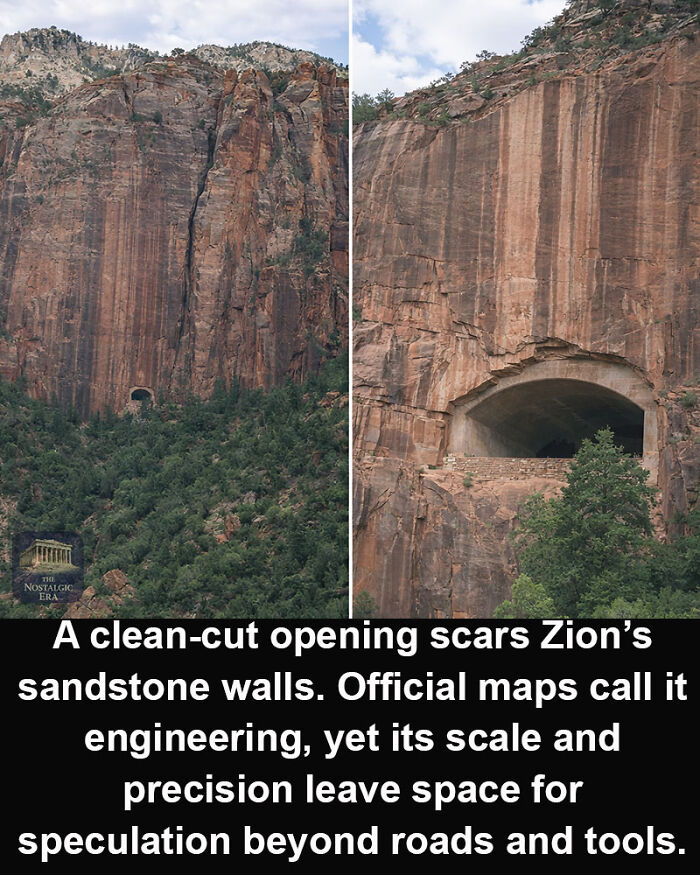

At Zion National Park, towering sandstone cliffs dominate the horizon, shaped over millions of years by erosion and uplift. Yet embedded within these walls are tunnels that interrupt the geological narrative.

The most famous, the Zion–Mount Carmel Tunnel, was carved in the early 20th century to connect remote canyon routes. Its smooth curvature, uniform ceiling, and strategic placement stand in sharp contrast to the surrounding fractured rock. From a distance, the openings appear almost intentional in a way nature rarely produces.

Engineering explains how the tunnels were made and when. It does not fully explain why their presence feels so anomalous within such an ancient landscape. Some observers have suggested alternative possibilities, including hidden or secondary uses never documented. There is no evidence to support such claims, yet the visual tension remains. In a place defined by deep time, even modern interventions can feel strangely out of context.

© Photo: Echoes of Yesterday

#53

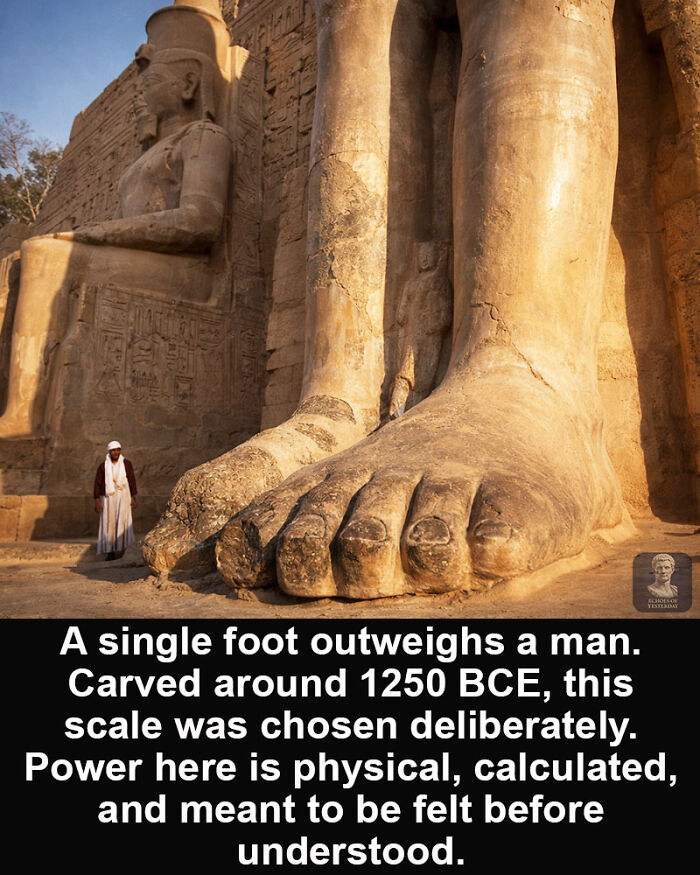

These statues were built to erase any sense of equality. At Luxor, during the reign of Pharaoh Ramesses II (1279–1213 BCE), colossal statues were commissioned to represent the pharaoh as a living god.

Carved in the 13th century BCE, during Egypt’s New Kingdom, they once stood at temples such as the Ramesseum, guarding sacred and political space.

Each figure depicts Ramesses II seated or in divine posture, his feet alone towering over human visitors. The scale is not symbolic, it is mathematical. The proportions are altered to enforce dominance, yet the carving remains precise down to toes, veins, and joints.

How blocks weighing dozens of tons were quarried, transported, raised, and finished with this consistency remains debated. The accepted methods work in theory, but leave little margin for error.

What is certain is intent. These monuments were designed to outlast rulers, cities, and belief systems. They succeeded.

#54

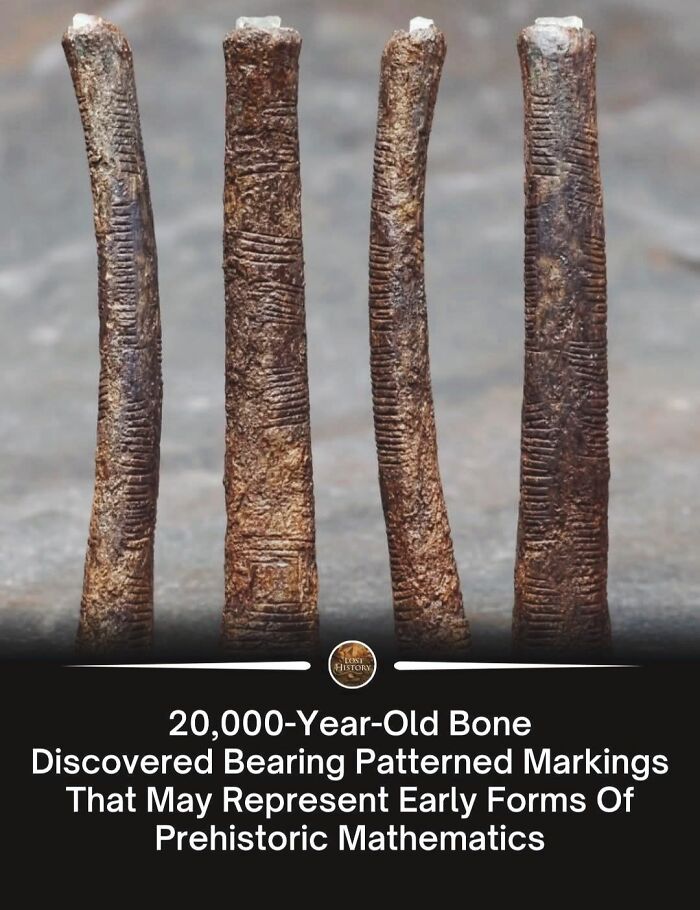

20,000-year-old bone has been discovered bearing patterned markings that some researchers believe represent early prehistoric mathematics. The artifact offers a tantalizing glimpse into the cognitive and symbolic abilities of Ice Age humans.

Archaeologists studying the bone note the repeated lines, scratches, and geometric arrangements etched into its surface. These patterns appear deliberate rather than random, suggesting intentional recording or counting. Some scholars propose that the marks could represent lunar cycles, tallying, or other primitive mathematical concepts, hinting at abstract thought far earlier than previously assumed.

The bone was likely a tool, a teaching object, or even a ritual item. Its markings demonstrate that early humans engaged not only in survival but also in observation, calculation, and symbolic expression. Each line invites curiosity: who created it, for what purpose, and how sophisticated was their understanding of numbers or patterns?

Beyond mathematics, the artifact evokes mystery. It connects us with individuals who lived tens of thousands of years ago, whose lives, knowledge, and intellectual curiosity have been frozen in time. The bone bridges millennia, showing that even in a harsh Ice Age world, humans sought to understand, organize, and interpret their environment in systematic ways.

This 20,000-year-old bone reminds us that history often hides in small details. Patterned markings preserved for millennia reveal early ingenuity, abstract thinking, and the enduring human drive to explore the mysteries of numbers, time, and life itself.

© Photo: Giv Veerly

#55

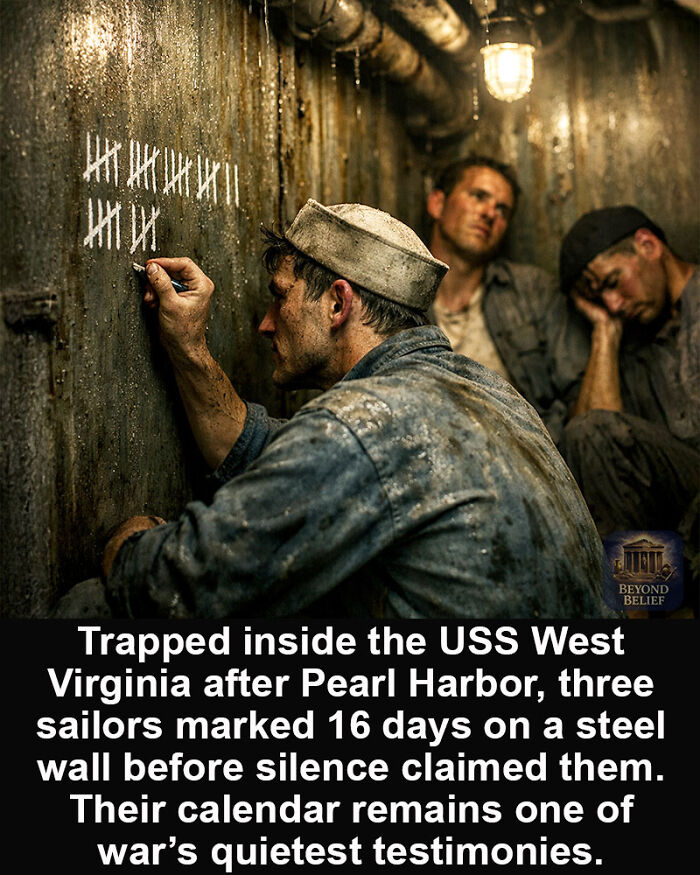

After the attack on Pearl Harbor, the USS West Virginia sank to the harbor floor, torn open by torpedoes and bombs. While many sailors died instantly, some survived the initial chaos, sealed inside dark compartments deep within the ship.

Months later, during salvage operations, workers discovered one such space. Inside were the remains of three sailors. On the steel wall beside them, a crude calendar had been scratched by hand.

Sixteen days were marked, one by one. These men had lived far longer than anyone realized, enduring darkness, rising water, limited air, and the slow certainty that help was not coming.

They did not persih in combat or explosion. They met their demise waiting. The calendar they left behind transformed their deaths from statistics into a human story of endurance, hope, and silence. It stands today as a reminder that the cost of war is not always loud. Sometimes, it is measured quietly, line by line, on cold steel.

© Photo: Beyond Belief

#56

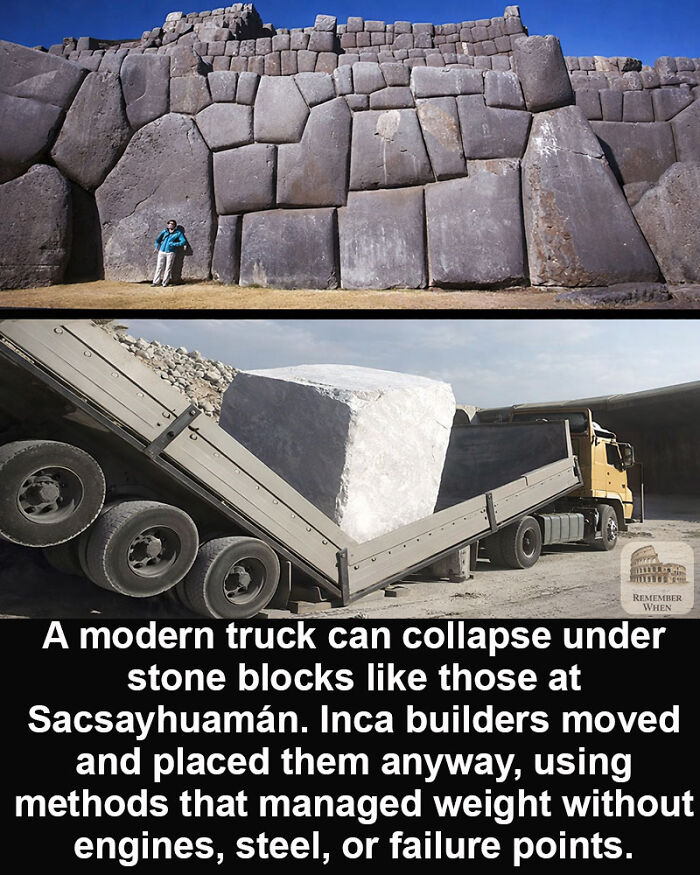

The contradiction is mechanical, not mythical. At Sacsayhuamán, above Cusco in Peru, Inca builders in the 15th century handled limestone blocks weighing tens, sometimes over a hundred tons. The image of a modern vehicle breaking under a comparable load reframes the discussion.

These stones were not dragged casually. They were shaped, moved uphill, rotated, and seated with precision that tolerates no adjustment after placement. Modern engineering relies on steel frames, hydraulics, and reinforced axles to manage such mass. None of these existed here.

Archaeology points to ramps, rollers, ropes, levers, and coordinated labor. These are valid principles, yet the exact execution remains undocumented. No surviving tools match the demands implied by the finished structure.

What stands at Sacsayhuamán is evidence of applied technology, not brute force alone. The stones behave as proof of systems that worked reliably at extreme limits. The methods succeeded so completely that only the results remain, leaving the engineering logic intact but partially invisible.

And there is one more uncomfortable detail: some evidence suggests the massive megalithic foundations at Sacsayhuamán may predate the Inca, who appear to have built more rudimentary structures atop earlier walls, a difference in technique still visible today. But that’s another discussion for another day.

© Photo: Remember When

#57

This site breaks the sequence history relies on. Göbekli Tepe, located in present-day southeastern Turkey, was constructed between circa 9600 and 8200 BCE, at the very beginning of the Neolithic period.

The builders were still hunter-gatherers. Yet they carved and erected massive T-shaped limestone pillars, some over 5.5 meters tall and weighing 15–20 tons, arranged in precise circular enclosures.

The pillars are carved with reliefs of animals, symbols, and abstract forms, repeated with consistency across multiple structures. No evidence of permanent dwellings surrounds the site. No clear signs of farming at the time of its earliest phase. The labor required implies organization, planning, and shared purpose on a scale that should not exist this early.

Most striking is what came next. After centuries of use, the entire complex was deliberately buried.

Not destroyed. Not abandoned.

Sealed.

Whatever Göbekli Tepe was meant to anchor, it was important enough to hide, intact, from the future.

#58

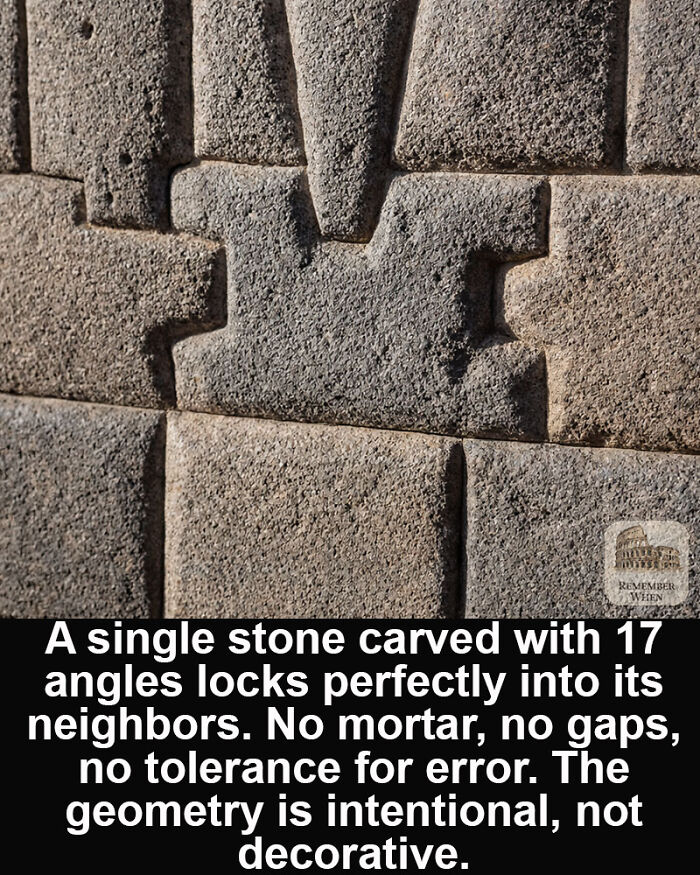

This block was never meant to stand alone. Known as the seventeen-angled stone, it forms part of Inca masonry in Cusco, Peru, created during the Late Horizon period, roughly the 15th century AD.

The tension lies in control. Andesite blocks were shaped so tightly that mortar was unnecessary. Each angle serves a purpose, distributing weight, resisting earthquakes, and locking neighboring stones into a single system. The seventeen-angled stone is not exceptional because it is complex, but because it works.

No metal tools, wheels, or written blueprints survive from Inca builders. Archaeology points to stone hammers, abrasion, and patient fitting through trial and removal. That explains method in theory, but not the level of consistency achieved across entire walls.

This stone is evidence of a mindset, not a trick. Geometry here is practical knowledge embedded in labor. The builders left no manuals. They left results, precise enough to endure centuries of stress without needing explanation.

#59

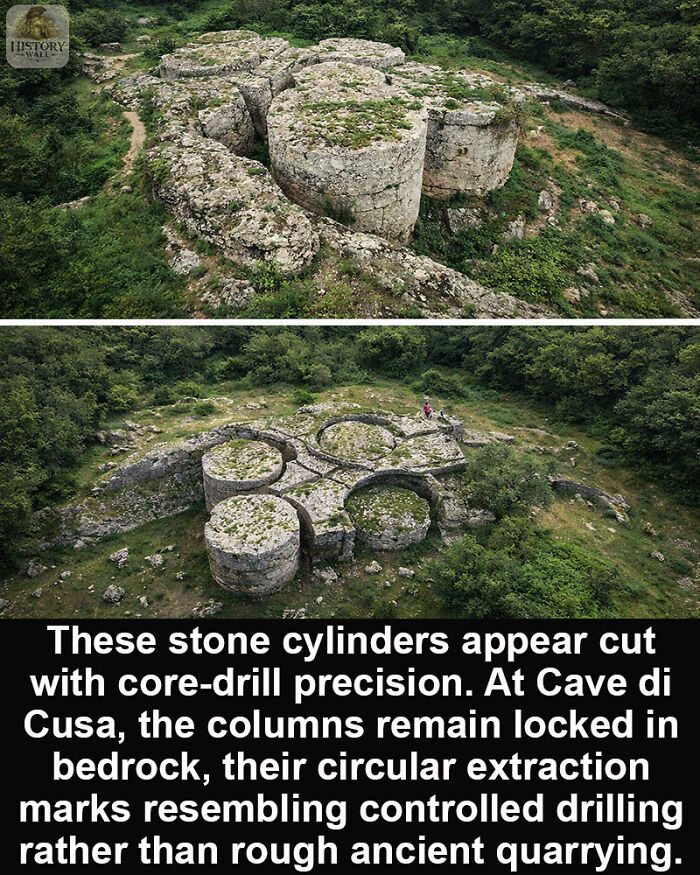

The quarry reveals a method that looks more familiar than expected. At Cave di Cusa in western Sicily, ancient limestone columns from the 5th century BCE remain partially carved directly from bedrock. Intended for the Greek city of Selinunte, these massive cylinders were left unfinished when work abruptly ceased, preserving the extraction process in place.

One detail dominates the site. The columns were separated using repeated circular cuts that strongly resemble the action of core-drills, producing consistent diameters over large stone volumes. These marks are not incidental. They define the entire method of extraction before transport ever began.

Archaeology explains the site as the product of Greek quarrying with iron tools and organized labor. That accounts for purpose and scale. It does not fully resolve how such drilling-like precision was maintained across multiple columns.

The columns were never installed. The process was never hidden. What remains is a rare view of ancient stoneworking frozen at the moment where technique becomes harder to explain than intention.

© Photo: Nouza Expla

#60

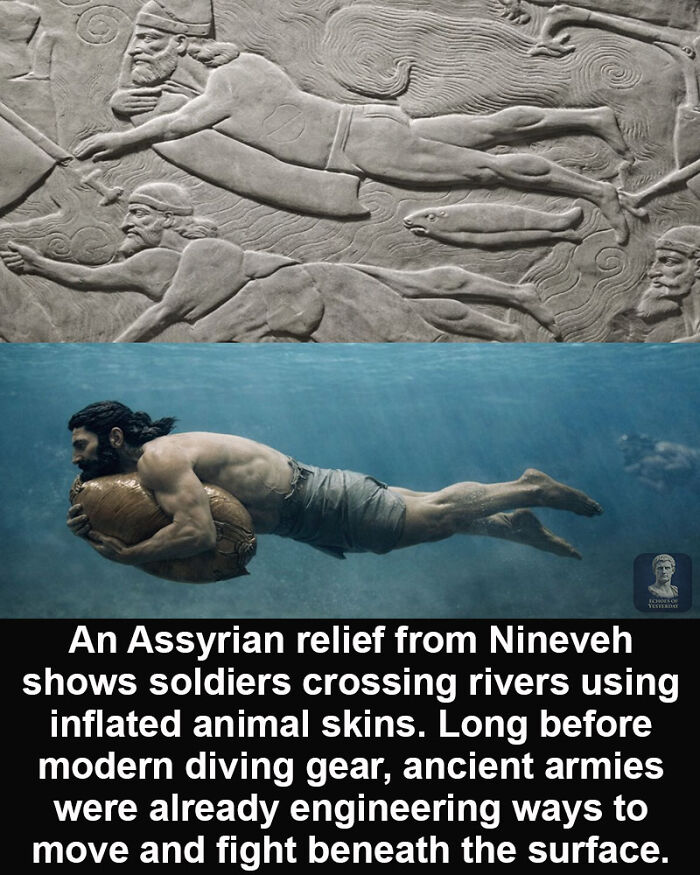

Around 700 BC, in the Assyrian heartland, rivers were not obstacles but tactical spaces. A relief from Nineveh shows soldiers suspended in water, gripping inflated animal skins as flotation devices. The scene appears calm, almost effortless, yet it captures a deliberate solution to a deadly problem.

These figures are not drowning. They are crossing. Air-filled skins kept bodies buoyant while weapons and supplies were guided alongside. The method allowed troops of the Assyrian Empire to move silently, bypass defenses, and extend campaigns beyond natural barriers. Stone preserves a moment of applied knowledge, not theory.

What makes the relief striking is intent. This was not improvisation in crisis, but a practiced technique carved into official art. The Assyrians chose to record it, suggesting pride in mastery over terrain and water alike.

Whether viewed as early military diving, tactical swimming, or symbolic display, the image connects ancient strategy with modern exploration. The boundary between land and water was already being negotiated

© Photo: Echoes of Yesterday

#61

The boundary between eras is not abstract. It has a location. The Chicxulub crater lies buried beneath the Yucatán Peninsula and the Gulf of Mexico, formed 66 million years ago when a massive asteroid struck Earth. Measuring roughly 93 miles in diameter and reaching depths near 12 miles, the crater ranks among the largest confirmed impact structures on the planet.

One detail stands out. The impact occurred in a region rich in sulfur-bearing rock, amplifying the environmental collapse. Debris circled the globe, temperatures plunged, photosynthesis stalled, and ecosystems failed in sequence. Dinosaurs disappeared, not slowly, but abruptly.

Geophysics, drilling cores, and shock-quartz confirm the event. What remains debated is not the impact itself, but how close Earth came to irreversible collapse. Chicxulub is not just a crater. It is the thin line where dominance ended and survival began.

© Photo: Remember When

#62

In October 2021, the sea returned a contradiction. Violence emerged from stillness. Off Israel’s northern coast, a 900-year-old iron sword surfaced from the seabed, preserved where waves had erased memory but not metal. Nearly four feet long, the weapon dates to around 1100 AD, the era of the Crusades, when faith and conquest traveled together toward the Holy Land.

The sword is believed to have belonged to a Crusader knight, likely lost during a coastal journey or skirmish. Its survival owes nothing to intention. Buried beneath sand and saltwater, the iron avoided complete corrosion, locked away from air and human hands. What remained was not a relic displayed for glory, but an object abandoned by circumstance.

This find does not recount a single battle or name a fallen owner. It offers something less complete and more unsettling, a direct link to movement, risk, and belief carried across dangerous seas. The blade endured. The story around it remains fragmented.

© Photo: Nouza Expla

#63

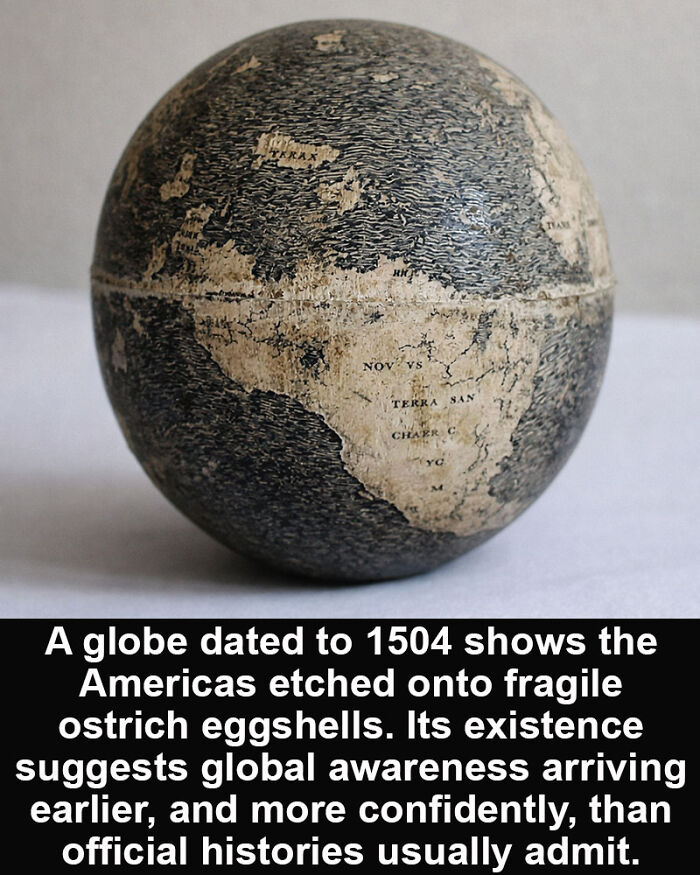

This object sits uncomfortably early in the story of world mapping. Dated to 1504, the so-called ostrich egg globe is widely regarded as the oldest known spherical depiction of the Americas, created only years after European contact.

The globe is constructed from two joined ostrich egg shells, their fragile surface carefully engraved with coastlines, names, and oceans. South America appears clearly labeled, not as rumor or suggestion, but as a defined landmass. That confidence is the tension. Cartographic certainty seems to arrive faster than exploration narratives imply.

Some scholars have proposed a connection to Leonardo da Vinci, based on stylistic and technical similarities, though no definitive attribution exists. What is certain is the skill required to engrave such detail onto an eggshell without destroying it.

The artifact reflects a moment when geographic knowledge, ambition, and secrecy overlapped. It records a world still being claimed, mapped, and interpreted, faster than its story could fully be told.

© Photo: Nouza Expla

#64

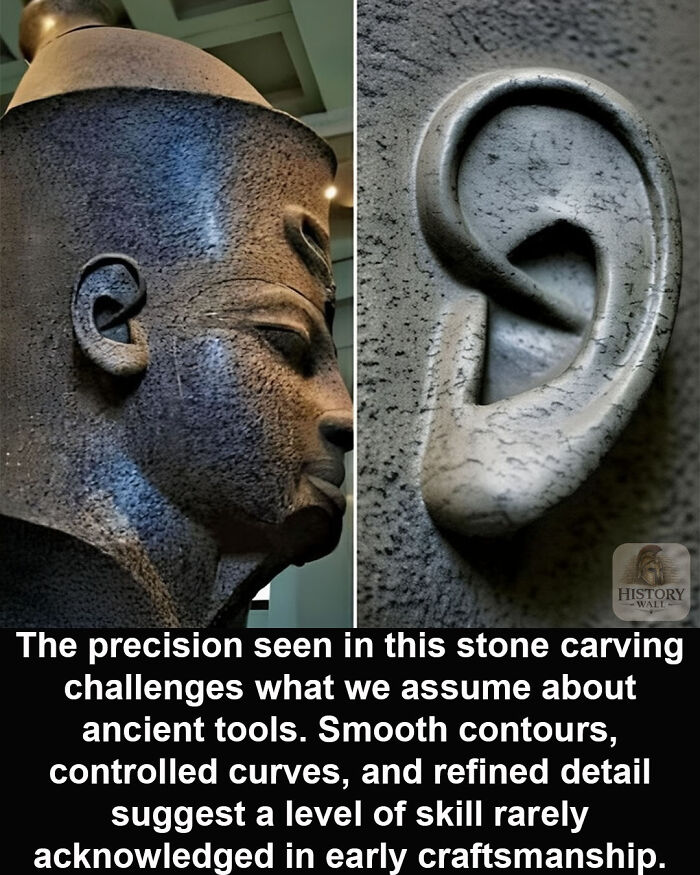

The precision visible in this carving is not accidental. The smooth transitions, balanced proportions, and carefully shaped contours, especially around the ear, indicate deliberate planning rather than rough stone work.

Such sculptures are commonly associated with ancient Mesoamerican cultures, often linked to the Olmec civilization, active more than 2,500 years ago. These works were created without metal tools or modern abrasives, relying instead on stone implements, abrasion, and patient repetition.

What continues to raise questions is not whether this was handmade, but how artisans achieved such consistency and refinement using limited materials. The carving suggests highly developed craftsmanship, often underestimated rather than unexplained.

© Photo: Nouza Expla

#65

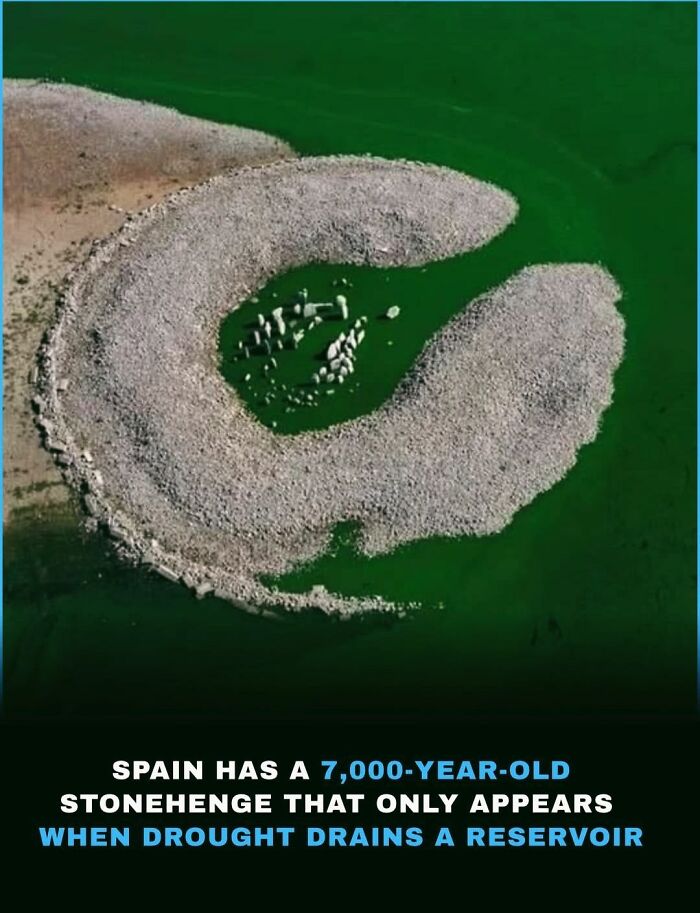

During periods of severe drought, an extraordinary prehistoric monument re-emerges from the waters of the Valdecañas reservoir in western Spain: the Dolmen of Guadalperal, often called the “Spanish Stonehenge.

This megalithic circle dates back roughly 5,000 to 7,000 years, making it older than Stonehenge and even older than the Egyptian pyramids. Built from large upright stones arranged in a ceremonial formation, it once stood on dry land near the Tagus River before being submerged in the 1960s when the reservoir was created. Most of the time, the monument lies hidden underwater, protected and imprisoned at the same time.

Only when water levels drop does it reveal itself again. The Dolmen of Guadalperal is believed to have had ritual or astronomical significance, reminding us that long before written history, people were already shaping landscapes with monuments meant to endure for eternity even if today they only surface when nature allows.

© Photo: Lina Wijayanti

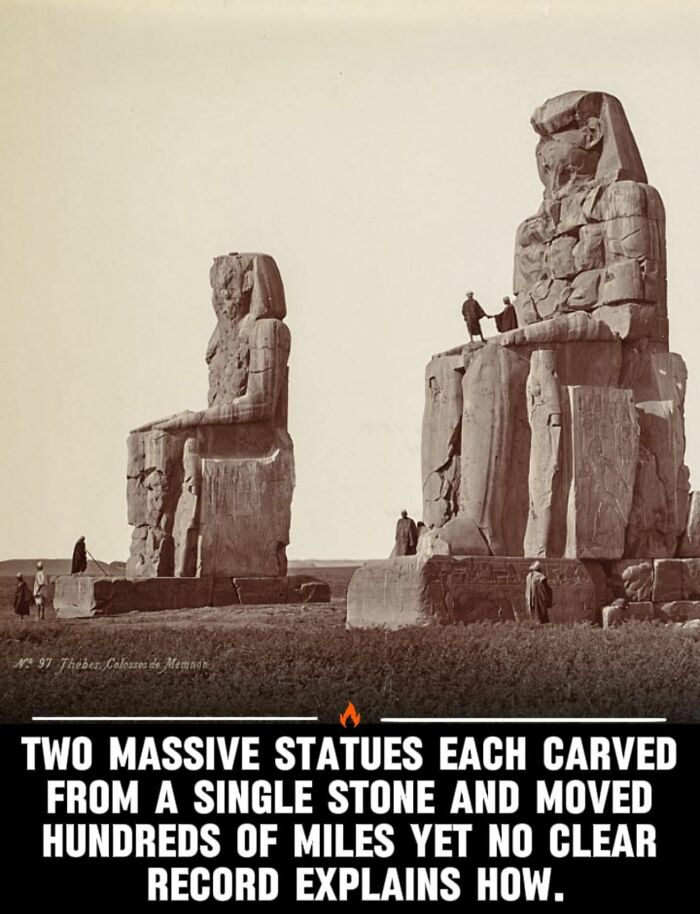

#66

The Colossi of Memnon are two massive stone statues standing on the west bank of the Nile near modern-day Luxor, Egypt. Each statue rises about 60 feet tall and weighs over an estimated 700 tons, carved from single blocks of quartzite. The stone was quarried near Cairo, more than 400 miles away, then transported over land to Thebes around 3,400 years ago during the reign of Pharaoh Amenhotep III. No inscriptions or records describe how blocks of this size were moved such distances without cranes or wheeled transport. Despite centuries of study, the logistics behind their relocation remain uncertain.

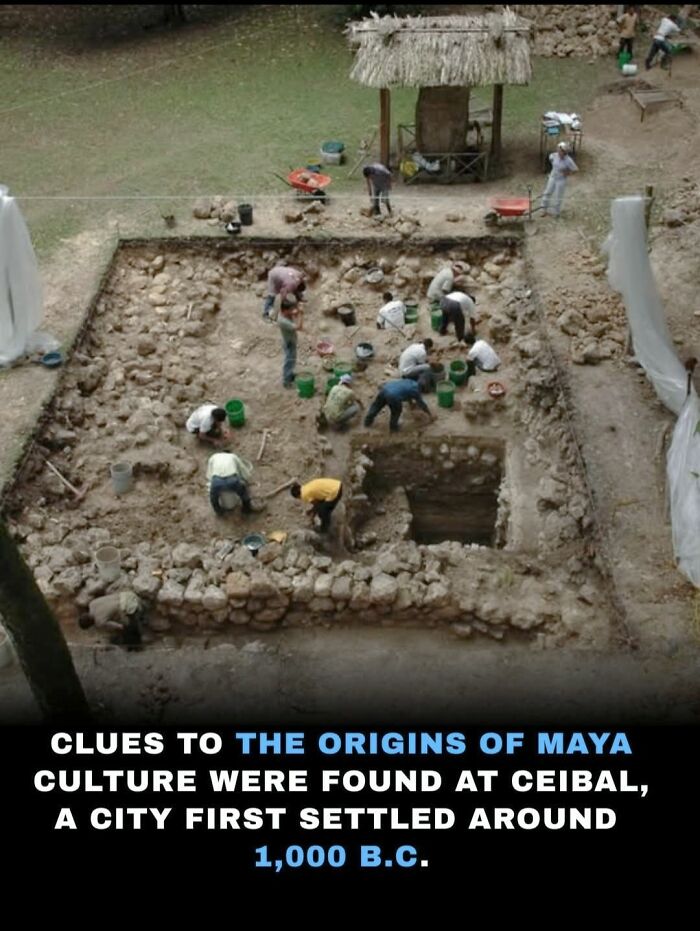

#67

Archaeologists have uncovered important evidence about the origins of Maya culture at the ancient city of Ceibal, located in what is now Guatemala.

The site was first occupied around 1,000 B.C., making it one of the earliest places where researchers can trace the beginnings of Maya civilization. Excavations show that Ceibal played a key role during a formative period, when early communities were developing new religious practices, political organization, and monumental architecture.

The discoveries suggest that many ideas later associated with classic Maya culture—such as ceremonial centers, ritual gatherings, and shared artistic traditions—were already taking shape here.

Rather than emerging suddenly, Maya civilization appears to have grown gradually from these early experiments in social and religious life. Ceibal offers a rare window into that critical moment when scattered communities began transforming into one of the most influential cultures of ancient Mesoamerica.

© Photo: Lina Wijayanti

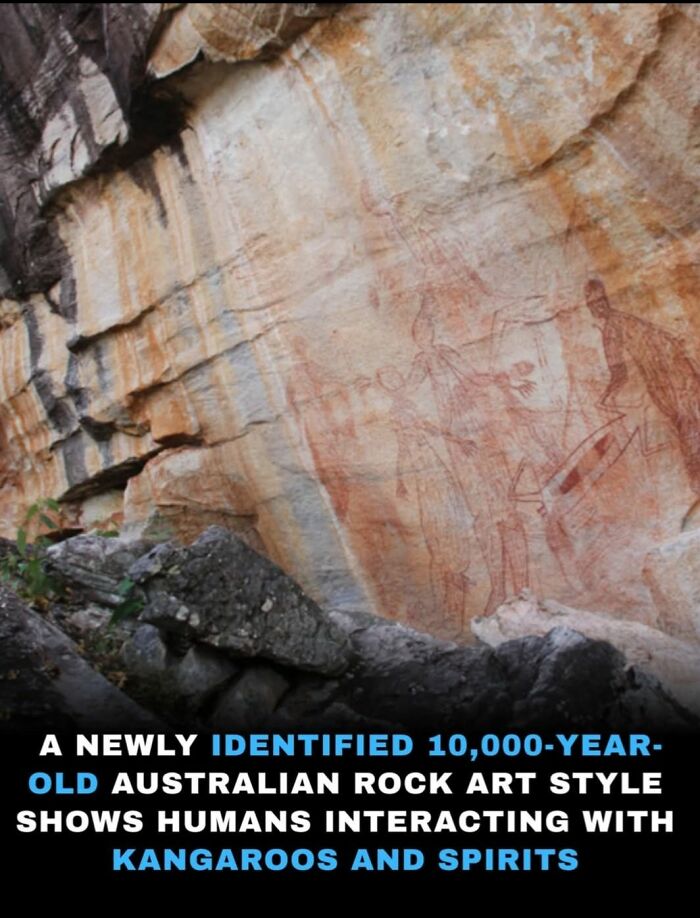

#68

In Australia’s West Arnhem Land, archaeologists working alongside Aboriginal Traditional Owners have identified a previously unknown rock art style that is around 10,000 years old.

This newly recognized tradition features striking scenes of humans interacting with animals such as kangaroos, often combined with supernatural or spirit-like elements. The artworks suggest a rich symbolic world in which everyday life, hunting, and the spiritual realm were deeply connected.

Because the research was done in partnership with Traditional Owners, the discovery also highlights the importance of Indigenous knowledge in understanding ancient landscapes and their meanings. The identification of this distinct style adds a new chapter to the already long and complex history of Australian rock art, which is among the oldest in the world.

These paintings are not just images on stone they are enduring records of belief, storytelling, and relationships between people, animals, and the spirit world stretching back ten millennia.

#69

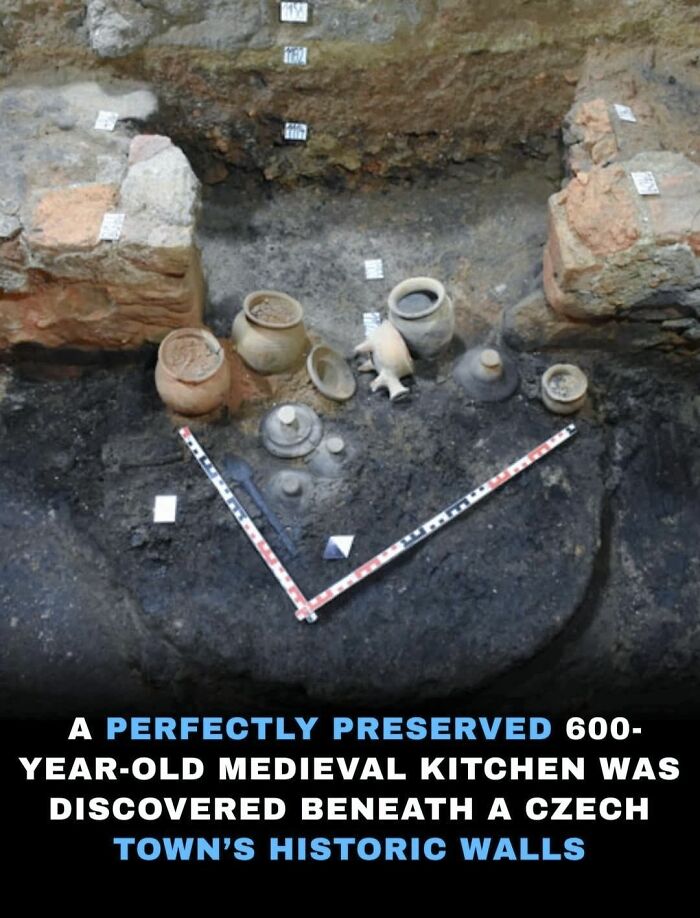

Archaeologists in the eastern Czech Republic have uncovered the remarkably well-preserved remains of a 600-year-old kitchen near the medieval walls of the historic town of Nový Jičín.

Unlike many sites where only foundations survive, this discovery offers a rare glimpse into the working heart of a medieval household. The layout and surviving features reveal how food was prepared, stored, and cooked centuries ago, turning everyday domestic life into a tangible archaeological record. Finds like this are especially valuable because kitchens were central to daily routines, yet they are often poorly preserved or overlooked.

This one, however, seems frozen in time, allowing researchers to reconstruct not just architecture, but habits, technology, and rhythms of life in the late Middle Ages. It’s a reminder that history isn’t only written in castles and churches—but also in the humble spaces where people cooked their meals.

© Photo: Lina Wijayanti

from Bored Panda https://ift.tt/tX8g4sj

via IFTTT source site : boredpanda