Many of us have a favorite movie or show—one that we could rewatch a hundred times without getting bored. And of course, we all have those favorite characters who steal the spotlight and stay with us long after the credits roll. But sometimes, it’s not just the characters that make a lasting impression—certain movie props become so legendary that they take on a life of their own.

Today, the Bored Panda team has scoured the internet to find exactly such props. From legendary weapons to unforgettable artifacts, these iconic objects have left a permanent mark on pop culture. Fans still remember them, quote them, and even dream of owning them. Keep scrolling to check out some of the coolest and most unforgettable movie props of all time!

#1 The Lightsaber, Star Wars (1977)

Roger Christian, set decorator: “When I saw Ralph McQuarrie’s painting, and George’s description of the lightsaber, I knew this would be the symbol of the film. It was obvious. He had invented something that everybody in the world would want.

“But I couldn’t find anything that felt right. It drove me mad. We had to get this prepared, and I was getting worried. The special effects made some [flashlight]-like ones but they just didn’t cut it. George rejected them. I was only looking for a found object, and I couldn’t quite find the weight that I knew this handle had to have.

“In desperation one day,I was making Luke’s binoculars, I found two different camera parts and I stuck them together with super glue. I needed two lenses to stick on the front and there was a photography shop in London which we always rented all our camera equipment for movies for so I went there and was buying a couple lenses and then I asked the owner, ‘Listen, have you got anything that might be interesting — I need a kind of a handle for a weapon. Have you got anything I could look at?’ And he said, ‘Look over there, there are some boxes that are all covered in dust.’ Literally the first box I pulled out, there were these Graflex [camera] handles, there were about six of them in the box. And this would be like going in slow motion, the music is rising — I took them out and it was like finding the Holy Grail. They were beautiful objects. They even had a red firing button on it.

“I got in the car and raced back to the studios. I thought, I have to have a handle, I took the same section of rubber I put around the sterling, stuck it as a handle around it. I found a piece of calculator where by the numbers were magnified, and it was like bubble strip — it perfectly fitted the grip. And I just held it in my hand and thought, this is it. I called George and said, you better have a look. He came and took it in his hand and smiled. And that’s more than approval with George. You’ve hit gold if you get a smile.

“[To make the blade,] a friend of mine who I was doing some art exhibitions with, we painted projection material onto wood and we were using it as a reflector … We took a wooden dowel, drilled out a few of the Graflex light sabers that I had made, stuck it in the end, and he put it slightly off center, the motor, so the blade would give a little bit of a wobble. It picked up light, enough to rotoscope some of the scenes … So the one I made [cost] about $12.”

Image credits: Thrillist Entertainment

#2 Wilson, Cast Away (2000)

Robin L. Miller, property master: “Wilson was in the script because, as I remember, [writer William Broyles Jr.] was down in Mexico and literally found a volleyball on the beach. Later we were told by psychologists that people, when they’re stranded and in moments of isolation, usually choose an inanimate object to talk to because they can’t handle being alone. The odd part of this was that the name ‘Wilson’ was in the script, and so I approached Wilson the company to make me volleyballs. Wilson wasn’t interested, at that point. Moviemaking had nothing to do with them. But I was very fortunate to find a woman there who, after I explained I was working with an Academy-Award-winning actor and an Academy-Award-winning director, the ball was called Wilson, for godsakes, and I needed blank ones, so I could make the face with Tom’s handprint. She got me 20 — only 20.

“I blew through 20 in a heartbeat. He went through all these incarnations, plus ones I could use for take after take after take. There were only five [hero props] used in the movie for up close shots.The aging on him changes over the course of the movie. His hair gets wrecked by the end. But we made them all last. I guarded them with my life. We were in Fiji, and then traveling to some island an hour and a half away from Fiji. The other nightmare was all those FedEx boxes — they fell apart in the humidity, so for all those takes, we were gluing them back together take after take. They were cardboard turning into soggy graham crackers. But the Wilsons were locked up. I practically took them to bed with me. They took a long time to fabricate, with the hair and the aging.

“When Tom made the original one, I put red tempera paint on his hand and he made the pattern on the ball, not on camera. He tried it and… it didn’t look great. So we did it again and again and again, and when we got one with enough room for the face, that became the template. We redid it on camera, and then we knew where we were headed because we came up with the concept three months earlier: how far his fingers needed to spread, what lines it needed to reach on the ball. Then the others were all hand-sewn, the hair was put in, and a scenic painter made five perfect matches, and then we had others for second, third, and fourth unit. Wilson had to be on every raft, and I wasn’t going to give them my best ones!

“The challenge was they all had to match. Towards the very end, the one that sinks, it’s so sad and so dirty. The hair is messed up. The one that ultimately sank, there were two (and remember, I only had five), but the effects department had to weight them to get pulled underwater. That was special — it aged the most. I don’t think we did many takes of that scene. It was the end of his journey.”

Image credits: Thrillist Entertainment

#3 Hannibal Lecter’s Mask, The Silence Of The Lambs (1991)

The eerie, cage-like mask that confines Hannibal Lecter in The Silence of the Lambs has become a symbol of the character’s terrifying presence and the unsettling nature of his crimes. Its design serves a practical purpose within the film’s narrative, protecting others from Lecter’s cannibalistic tendencies while allowing him to breathe and communicate. The mask’s open eyeline adds to its unnerving effect, enabling Lecter to maintain his piercing gaze and assert his psychological dominance over those around him.

The prop’s ability to dehumanize the character paradoxically heightens his menace, transforming him into a caged beast whose intellect and cunning remain undiminished by his physical restraints. This iconic status of the mask is further cemented by its prominent role in the film’s sequel, Hannibal, where it serves as a chilling reminder of Lecter’s past and the lingering threat he poses to society. Lecter’s use of the mask symbolizes the complexity of his character, blurring the lines between humanity and monstrosity.

Image credits: Kayla Turner

We’ve all noticed iconic props in some of our favorite films. Whether it’s the One Ring from The Lord of the Rings, the DeLorean from Back to the Future, or even the mesmerizing dresses in The Hunger Games, these objects become more than just set pieces—they become an unforgettable part of the story.

Some props are so legendary that even the actors can’t resist taking them home! Reese Witherspoon’s contract for Legally Blonde 2 allowed her to keep Elle Woods’ stunning wardrobe. Daisy Ridley was gifted a lightsaber from Star Wars, while Zac Efron took home his signature board shorts from Baywatch. But how exactly are these crucial props sourced and managed on set?

#4 The One Ring, The Lord Of The Rings Trilogy (2001-2003)

Grant Major, production designer: “Tolkien’s idea of the ring, though highly descriptive in its origin and the terrible power it has over its wearer, was described physically as being a simple golden band. This band is able to expand and shrink to fit the hand that wears it and when heated reveals a phrase in Black Speech: ‘One ring to rule them all, one ring to find them, One ring to bring them all and in the darkness bind them.’ “When first tasked with the design of this most important prop for The Fellowship of the Ring, I thought it would probably take forever to agree on its look with the director, producers, the studio, LOTR experts, and fans all weighing in.

You can imagine the visual significance to the film, the marketing, and other spin-offs, and how this iconic object would have to endure all sorts of ongoing scrutiny and re-production. “It’s interesting to understand that, at this phase of development in late 1998, the film project was completely under the radar, with none of the hype that surrounds it now. And Peter Jackson had the last word in all these design decisions. As it transpired, the overall design concept was quick and easy, one of the producers, Rick Porras, was about to be married and the ring he had chosen was identified as a good starting point for ‘The One Ring.’ Its profile was perfectly bulbous and ‘weighty’ and had a significant ‘historic’ look, was well proportioned and simple enough to carry the phrase on its internal and external surfaces.

Alan Lee produced some additional sketches of the ring but it didn’t change significantly from this first idea. A local jeweler from Nelson, New Zealand, Jens Hansen, was chosen to make these ring props. After various prototypes were produced, a final version was chosen and then multiples were made (around 40, I understand) for the actors and doubles in various units, many more were made latterly for publicity and gifts. “There were also versions made for specific moments in the story; an extra large one (way over scale) was used for a super close up when placed on a table (also over scale) in Bag End to achieve a forced perspective effect.

Another version was made from a magnetic metal so that when dropped onto the floor inside the front door of Bag End it would appear heavy and not bounce. From memory, there was never a version with the glowing lettering — this became a visual effect. The lettering itself was a direct copy of that found in the book. But it was such a privilege help to bring this iconic prop to life and see how it has now become the definitive version for this movie phenomenon.”

Image credits: Nathan Johnson

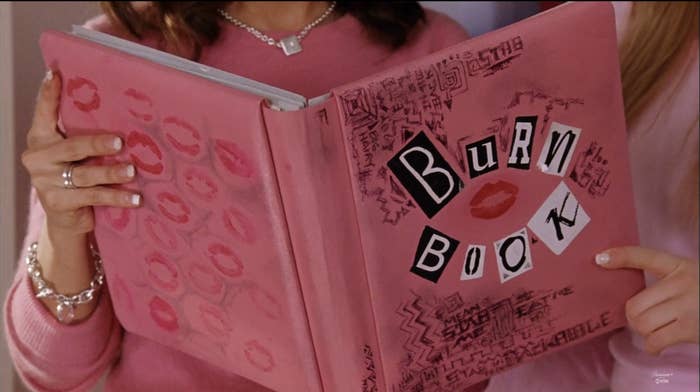

#5 The Burn Book, Mean Girls (2004)

The Burn Book in Mean Girls is a scrapbook created by “The Plastics” to document rumors and insults. It needed to look both handmade and detailed, fitting the early 2000s high school aesthetic while capturing Regina George’s stylish, superficial personality.

The production design team, led by Carol Spier, started with a basic scrapbook and transformed it with bright pink tones, bold lettering, and embellishments, creating a stylish yet sinister vibe. The props team filled it with handwritten insults, magazine clippings, gel pen doodles, and Polaroid photos, carefully balancing neatness and chaos to mimic high school work.

The production design team worked closely with the writers and director to ensure the Burn Book’s contents matched the humor and tone of Tina Fey’s screenplay. Some pages were intentionally exaggerated to maintain the film’s PG-13 rating. The original Burn Book is likely stored in Paramount’s archives and has been featured in exhibitions of movie props.

Image credits: Everly Home Staging

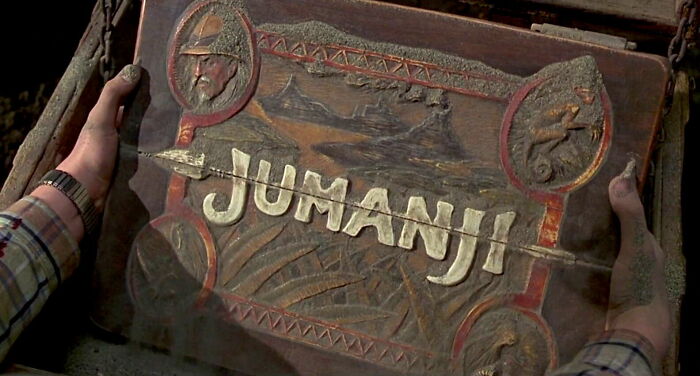

#6 The Game Board, Jumanji (1995)

Joe Johnston, director (in a letter of provenance written for auction): “Cast foam carry board[s were] used in scenes where the actors (usually Robin Williams) had to walk outdoors or move around in the set with the closed Jumanji game. The hero boards that were used for close shots were made of wood and were quite heavy. To reduce the risk of a hero board being dropped and damaged, a mold was made from one of the hero boards and reduced-weight carry boards were produced. There were also molded rubber stunt boards that were only used when an actor had to run or fall with a closed game board, or interact with it in some potentially dangerous way. As far as I know, there were at least two hero boards constructed, one with a false back to allow the magnetized movement of the game pieces. There were at least three carry boards produced. To the best of my recollection, one of the carry boards was destroyed in the scene where the house splits in two. There were four or more rubber stunt boards.”

Image credits: Thrillist Entertainment

To understand the behind-the-scenes magic of movie props, Bored Panda spoke to Rahil Patel, a seasoned prop coordinator from India with over three decades of experience in the industry. His insights into the world of props were nothing short of fascinating.

“It might seem like an easy job, but let me tell you—it’s anything but that,” Rahil shared. “Sourcing the perfect prop isn’t just about finding an object. It’s about ensuring it fits the movie’s setting, matches the director’s vision, and serves its purpose seamlessly in the scene.”

#7 The Snitch, Harry Potter And The Sorcerer’s Stone (2001)

Stuart Craig, production designer: “Like so many things in the Potter world, the concept is really all in the original text, in J.K. Rowling’s description. She says the snitch is the size of a walnut. A golf ball is substituted in practice. It has fluttering silver wings, which must be completely hidden while at rest to achieve the small size. Gert Stevens was the concept artist who did the final illustration. Pierre Bohanna’s prop making team made it… a really delicate piece of mechanical engineering. The wings were stowed in deep narrow channels curving across the surface, apparently surface decoration but secretly hiding the wings.”

Image credits: Thrillist Entertainment

#8 Indiana Jones’s Hat

Indy’s hat wasn’t just any fedora; it was custom-made by Herbert Johnson Hatters in London to look rugged but cool. Harrison Ford’s insistence on wearing it all the time led to it becoming as iconic as his whip. The original hat has been auctioned off, with some replicas and originals selling for over $500,000.

Image credits: Jamie "J" Cruz

#9 The Box Of Chocolates, Forrest Gump (1994)

Robin L. Miller, property master: “Bob [Zemeckis, director] loves Americana. He loves a retrospective feel. A movie we’re doing now takes place in 2003 and still he wants the props to feel nostalgic — we’re not cutting edge 2003, but we’re in the ’90s. It’s that kind of comfort.

“The box of chocolates had all the selections. Russell Stover Chocolates was an icon. There was the Whitman’s Sampler… and I’m not sure why we didn’t go with that. Maybe [Bob] didn’t like the box. But Russell Stover’s was emblematic. Everyone knew it. It didn’t stand out, which is actually the best prop in the world.

“What’s funny is the studio was adamant of getting the box of chocolates. When you wrap a [movie], everything gets logged in case they have to do reshoots. You give them all the documentation so they can remake it. I gave it to them, and five others, but I told them, you can buy this. That’s so rare, actually. The box was the real thing, and hadn’t changed in a long time.”

Image credits: Thrillist Entertainment

“There are different kinds of movies, and in some, props are just that—props. If a dinner scene needs a plate, we get a plate. But then, there are fight scenes or intricate dance numbers where the prop plays a much bigger role. For example, if a character uses a fake knife, we have to make sure it looks as close to a real one as possible while still being safe.”

#10 The Talkboy, Home Alone 2 (1992)

Roger Shiffman, founder of Zizzle L.L.C. and former President of Tiger Electronics: “I worked directly with John Hughes. He came to my office a few times. His original concept in the script was for Macaulay Culkin to have a gun. I said, ‘Look you can’t have a gun at the airport. It just doesn’t fly at O’Hare.’ So I told him to let me work on it. “We actually designed the Talkboy ourselves, which is why it has the design it has, with the grip where he could slide his hand into and the extending microphone so it looked more lifelike. We had not [done a recorder before that] and what was interesting is how big a deal it was for us and Fox. Fox made the introduction with John, but I made a deal with them for a modest royalty I’d continue to build the brand. We went on to do a tremendous amount of volume — there are videos of people fighting over them — but the big success only came when they sold the VHS tape. It was the largest distribution, I think 10 million tapes, and every one had a printed brochure for Talkboy, saying it was a real product you could get.”

Image credits: Nathan Johnson

#11 The Neuralyzer, Men In Black (1997)

In the world of Men in Black, the neuralyzer stands out as a quintessential piece of technology that has left a huge impact on pop culture. This unassuming, pen-like device possesses the power to erase the short-term memory of any witness to extraterrestrial activity, ensuring that the secretive work of the MIB remains hidden from the public eye. The neuralyzer’s sleek, futuristic design perfectly encapsulates the film’s blend of science fiction and comedy, making it an instantly recognizable prop that has become synonymous with the franchise.

The neuralyzer’s crucial role in the narrative elevates it from a mere gadget to a key plot device, showcasing its originality and narrative significance within the film’s universe. Its iconic status as a memory-wiping tool seamlessly integrates into the story, distinguishing it from more conventional weapons commonly seen in Hollywood blockbusters. This unique feature underscores its impact on the audience, contributing to its lasting impression.

Image credits: Kayla Turner

#12 The Zoltar Machine, Big (1988)

James Mazzola, property master: “I was Zoltar. I was inside that machine. I built it for the specs of my body. And I sat in the whole thing and designed it so I could fit in there and do all the little apparatuses. You know when the quarter goes down the chute? I had a screen in front and could look at Tom [Hanks] to see when he did his actions. We designed the thing and our fabricator on 23rd St — which is no longer there — built it. It’s all handmade. We actually just cut it up and painted it and taped it and I did the mechanics to it. So you know it was a lot of people involved in the thing, and it came out really well. The timing of that quarter sliding into his mouth was a challenge. Inside I had a whole board with all kinds of levers. I was in good shape and I just knew the systems, so it worked each time and we didn’t have to keep doing take after take. I knew exactly what they wanted, so why teach somebody to do it?”

Image credits: Thrillist Entertainment

“For period films, the challenge is even bigger,” Rahil explained. “You can’t just pick any antique-looking object and place it in the scene. Every single detail needs to be historically accurate—right from the fabrics used in costumes to the kind of weapons, jewelry, or even furniture shown on screen.”

#13 The Nunchaku, Game Of Death (1978)

As detailed for Spink’s “Bruce Lee 40th Anniversary Collection” auction: “Lee personally designed this iconic weapon to match his celebrated yellow and black Game of Death jumpsuit. Designed to deliver matchless combat sequences during Lee’s electrifying nunchaku battle with senior student and co-star, Dan Inosanto, the design was conceived to facilitate the lightning-fast solo displays Bruce would deliver to camera. Unique amongst all Bruce Lee’s nunchaku, the nunchaku is built from lightweight lacquered wood and the sticks are connected by a fortified cord. By requesting this design, Bruce ensured that the nunchaku would move with the maximum speed and fluency in his skilled hands.”

Dan Inosanto, actor (Pasqual) (in the documentary I Am Bruce Lee): “In 1964, I introduced the nunchucks to Bruce Lee. At the time he thought it was a worthless piece of junk. When he moved to the LA area, I taught him how to use it. In three months he swung it like he’d be swinging it for a lifetime … In the short time, every child was using this. It became a household product. Now it’s outlawed in California.”

Image credits: Thrillist Entertainment

#14 The Fuzzy Pen, Legally Blonde (2001)

Robert Luketic, director: “Amongst the most ludicrous things we talked about on the movie were the color of blonde hair — what is blonde hair? — the breed of dog (and when I met Bruiser that was very obvious), and then what this pen was going to look like. This pen was brought to my attention by my art department. My eye went immediately to the pink puffy ball. I had never seen anything like it. That was the pen you bring to the first day of Harvard Law. She did things on her own terms, in her own way and her own world. She wasn’t going to conform. That pen said it all. And it’s something the writers and I hear about all the time: ‘The movie encouraged me to go to law school. Look at me, I can still be who I want to be.’ Women say it was empowering and freeing. And [the pen] slapped me in the face. It was so apparent.”

Image credits: Thrillist Entertainment

#15 Ruby Red Slippers, The Wizard Of Oz (1939)

In 1939, Dorothy (Judy Garland) was able to return home in The Wizard of Oz by clicking the heels of her unmistakable ruby red slippers. There were probably about six or seven pairs of red slippers used during filming and there are four known remaining pairs today. However, at least one of them is unaccounted for. One of the pairs from The Judy Garland Museum in Grand Rapids, Minnesota was stolen in 2005.

Theories abounded about the slippers whereabouts. Some speculated the thief threw them into the Tioga Mine Pit Lake. Others believed the criminal sold them on the black market. There were no leads on the slippers for several years, until an Illinois man was allegedly spotted bragging about how he was involved in the heist from the Garland Museum. The cops raided the man’s house but didn’t find the slippers. In 2015, an anonymous donor put up a $1,000,000 reward for the return of the slippers.

Then, in September 2018 – 13 years after the slippers were stolen – the shoes found their way home. Thanks to a 2017 tip to Detective Brian Mattson, the Grand Rapids Police Department, along with Minneapolis FBI agents, were able to track down the missing shoes. The details surrounding the recovery were not discussed.

Image credits: Ann Casano

And it’s not just about getting the right prop once. “We don’t have just one piece of a prop,” Rahil revealed.

“For most key props, we source multiple identical versions—usually seven or eight—because they often get damaged during fight sequences, misplaced on set, or taken by actors as souvenirs. We always need backups to maintain continuity.”

#16 The Chainsaw, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974)

Tobe Hooper, director: “I needed an old saw. A saw that had character from age. One of the investors in the movie happened to have an old saw in his garage. [We had] just that one. Of course production-wise, that’s almost unheard of. That thing could’ve been damaged, stolen, ruined.

Leatherface fell with it a couple of times. We were a bit cavalier about being careful with it. So we got another chain for the saw and took all of the teeth off it. Then we took the clutch out of the saw itself to see what would happen. If you rev the engine, the chain without that piece would naturally vibrate around in a circle. So the film only reads that it’s spinning.

That made it safe for running with it. “But when it came to a shot where we had to cut something with the saw, we had to put the clutch back in and the chain with teeth back on. It has to go through Leatherface’s pants when he falls at the end of the film. So the clutch goes back in and a piece of metal goes on his leg and underneath there’s meat wrapped in plastic with a lot of stage blood inside it. It ripped through the steak and down to the steel plate that heated to up to maybe 150 degrees because of the friction.

His reaction of pain was real. It burnt him. Not real real bad, but enough to make him jump. I didn’t want [the actors] calm at all. It was a miserable shoot, and that misery brought out pure and real fear. I later heard from [Gunnar Hansen] giving interviews that doing that final shot was his last opportunity to kill me, that he worked that dance up, swinging that saw close to me. It’s right up to the camera. So ending on that, just cutting to black at the peak of the hysteria was totally natural. You’re left breathless.”

Image credits: Nathan Johnson

#17 The Batarang, Batman (1989)

Terry Ackland-Snow, art director: “We did a rough design sketch of what was required, and then it got handed over to the special effects supervisor, John Evans, who made all the gadgets. We were working on it all together at the same time, giving Tim Burton exactly what he wanted Batman to have. [The batarang] was based on trying to fit the symbol of Batman — the idea was to have everything Batmobile-looking, the wings, that sort of thing. All the gadgets echoed each other.” John Evans, special effects supervisor: “I think we made about a dozen. We made some with fiberglass and some with polished aluminum. Anton [Furst]’s team had done all the designs, so he gave us the designs, and we took it from there. It was a simple thing to do. We just had to get the balance right so it could fly through the air.”

Image credits: Nathan Johnson

#18 Red Dress, Pretty Woman (1990)

The red dress in ‘Pretty Woman’ stands as a significant fashion icon. Worn by Julia Roberts, this dress is not just an article of clothing but a symbol of transformation and empowerment. It marked a moment in cinematic history where fashion and character development collided, influencing real-world fashion trends and societal perceptions of glamour and romance. The allure of the dress and its impact have been discussed in fashion circles, underscoring its enduring popularity and cultural relevance.

Image credits: Beatriz

“Continuity is key,” he continued. “Imagine a character holding a specific cup in a scene. If we lose that cup halfway through filming, we can’t suddenly replace it with a different one—it would break the audience’s immersion. That’s why having multiple identical props is crucial.”

#19 The Proton Pack, Ghostbusters (1984)

The Proton Pack from “Ghostbusters” was a prop designed to look like a piece of advanced technology. Its fictional purpose to capture ghosts was made believable through its detailed, pseudo-scientific design, capturing audiences’ imaginations and becoming a symbol of the franchise.

Image credits: Lifestyle trends

#20 Mechanical Shark, Jaws (1975)

The movie Jaws may have been released more than 35 years ago, but one of its most memorable props is still as popular as ever: a full-size mechanical shark head used in multiple scenes of Steven Spielberg’s 1975 blockbuster. The 17-foot prop—nicknamed Bruce after Spielberg’s lawyer, Bruce Ramer—has become a fixture at theme parks and film exhibitions around the world.

Image credits: Spur Creative

#21 The Hamburger Phone, Juno (2007)

Steve Saklad, Juno production designer: “The hamburger phone was actually in the very first script that Diablo Cody wrote. She spec’ed out the phone and based it on recollections of her youth. We found an obscure Japanese online website that had them, and we only got one. It was shipped from China. We were shooting in Vancouver, and the customs impounded it, because it qualified as some toy, and there were restrictions on toys going from China to Vancouver at the time, so it was actually imported to the US, to Seattle, and then somebody drove it up to Vancouver to get it past the customs ban.

“Jason Reitman, the director, was super specific about what it should look like. It was one of the very first set-dressing items that we searched for when we were putting together Juno’s bedroom. For about two weeks, our set decorator was sweating bullets until he found the thing that would please Jason. Jason was very much hands-on. Every single poster on the walls of Juno’s bedroom were approved by Jason and some of them were ones that Jason required us to get clearance for and put on the wall. Then he shot it so you saw it. He had beauty shots of the phone and the walls of posters.

“I wouldn’t say that there’s one awesome moment of her picking up the phone for the first time — it actually gets very little coverage in the movie. But that’s the whole point of the hamburger phone: It’s this inane kid thing crashing into a completely adult challenge, adult problem — that’s why it works so brilliantly: that’s encapsulated in one piece of plastic.”

Image credits: Thrillist Entertainment

When it comes to costumes, the same rule applies. “For a dance scene where a character is sweating or moving a lot, we usually have at least three copies of the same outfit,” he explained. “One is worn, another is kept fresh for hygiene purposes, and the third is a backup in case of any wardrobe malfunctions.”

#22 Big Ern’s Bowling Ball, Kingpin (1996)

Peter Farrelly, director: “We shot most of the bowling stuff in the Pittsburgh area. There are tons of old bowling alleys around Pittsburgh — in the Midwest, they bowl! But they’d never been changed, so they were just beautiful. Every town had one!

“We were scouting for the bowling alley and there it was, on a shelf. I said, we have to get his for Big Ern, so we bought it from them. When I first saw it, it looked like art, man. But [Bill Murray] did bowl with it, of course. The minute we handed it to him he was just tickled. And there was only one ball. Now it lives in Kings Alley in Boston, Massachusetts. They have a Kingpin wall.”

Image credits: Thrillist Entertainment

#23 The Mockingjay Pin, The Hunger Games (2012)

Dana Schneider, jewelry designer: “I could tell even before I was contacted [for the movie] that that design really struck home with a lot of the readers. That’s one of those things that you’re almost afraid to take on, because you just know how much people care. But I always like a good challenge. “There were a lot of technical things that had to be worked out, [like] getting the scale right. Because they were in the [book] illustration, I really needed to get the feathers just right. Getting the arrow to float free in the beak. [To carve the bird], I started with a very hard carving wax. By hand. No 3D modeling, no computer printing. The bird itself and ring are cast sterling silver. But for strength, the arrow ended up having to be made out of 14-karat gold. Silver’s just too soft. Then it all gets gold plated.

“There’s something about birds in flight. They’ve always had a history of hope and free spirit. I think that’s why I originally starting carving birds in my own jewelry work. But a lot of it really just boils down to a sense of freedom. Then adding the arrow to it I think is interesting because you add that extra element of, I don’t want to say self-defense, but fighting back. Without the arrow, it would just be a really pretty bird and you can draw whatever conclusions you want. But having the arrow in the beak definitely really makes it a symbol for courage, strength, all those good things.”

Image credits: Thrillist Entertainment

#24 The Hockey Stick Putter, Happy Gilmore (1996)

Perry Blake, co-production designer: “It was a totally fabricated prop. We started with the hockey stick, in terms of the size of it. The bottom part was, more or less, like a hockey stick, but we also wanted to make it flat and smooth. As far as I know, there wasn’t anything like this that existed — it’s not like you could go online and buy them, and I don’t remember anybody having them.

“We mocked them up and would bring them to director Dennis Dugan, and, you know, Adam is very involved in his movies, so he was testing them out and looking at them and deciding which one he liked best. We wanted to have one ‘prove-it’ shot that was like a 25ft putt, one where Adam actually made it. So the putter actually had to work.

“I remember the day we were shooting that scene, it was basically like, OK, we’re just gonna sit here, and Adam’s gonna shoot the ball from way back there until he makes it in. Everyone was betting on how many it would be: Is it gonna take him more than five shots? Is it gonna take him 10 shots? Finally, when he made it in, everybody went crazy. It was a lot of fun.”

Image credits: Thrillist Entertainment

“Beyond just sourcing and using props, storing and managing them is a whole other challenge,” Rahil added. “Props need to be maintained, cleaned, and sometimes even repaired daily. They can’t just be tossed aside once a scene is done.”

#25 The Heart Of The Ocean, Titanic (1997)

Peter Lamont, production designer: “I worked with a buyer, Ronald Quelch, and when we did On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, he knew John Asprey, who ran Asprey [& Garrard Limited]. On [Majesty’s] we wanted a vanity case, and we were allowed to borrow one, but if we marked it we bought it. No arguments. When we showed [director] Peter Hunt, there was a smaller box inside the case that he loved, and we mocked it up in the studio. It was awful. So John Asprey said, ‘Get me the imitation crocodile skin and we will make them for you,’ which we did. He fitted all the capsules inside. They did a beautiful job of them. Then in Octopussy we had the Faberge egg, and again, Ronald went to John, and he made them for us. So obviously when I was on Titanic, we wanted the ‘Heart of the Ocean,’ and I spoke to Ronnie and he spoke to John Asprey, and he made it. It was a one-off.

“For Jim [Cameron, director], everything had to look as much like Titanic as possible. There were so few photographs of the real Titanic, and a lot was copied after Olympic, a sister ship. I remember the first set we did was the parlor suite. It was a real struggle to get it ready. We put the last screw in the wall to hang the bracket with the lamp that came from Mexico City that night. Jim breezed in and said, ‘Looks right. Smells right.’

“The necklace wasn’t based on an old design, but it did need to be heart-shaped. The thing is, it was a rather deep stone. If you have a diamond, they’re always faceted, not cut off flat, because they won’t get any reflections. It was rather expensive and had to be made beautifully. We used a semi-precious stone and, when you looked at it, it had to have all the definition. Couldn’t be flat. Then behind the stone there’s a little cage that protects the stone from being damaged, and we had to have a jeweler remove it because the stone was quite big. Then a facsimile was made right at the very end so it could be thrown into the water.”

Image credits: Thrillist Entertainment

#26 The Jetpack, Thunderball (1965)

Bill Suitor, rocket belt pilot (on his website): “I was James Bond’s stunt double during the shooting in France 1965. My colleague Gordon Yeager and me both flew three flights. Later it was edited to one flight.”

“I began flying at Bell Aerosystems (later Bell Aerospace) in 1964 at the age of 19. The rocket belt had been developed by Bell for the US Army and part of their contract stipulated that they had to train a young man of ‘draft age’ with no previous flying experience. It just so happened that the inventor of the belt, Wendell Moore, was a family friend and neighbour. I was an architecture student at the time and not very happy, so when he said, ‘Hey kid, wanna job?’ I jumped at the chance.”

Image credits: Thrillist Entertainment

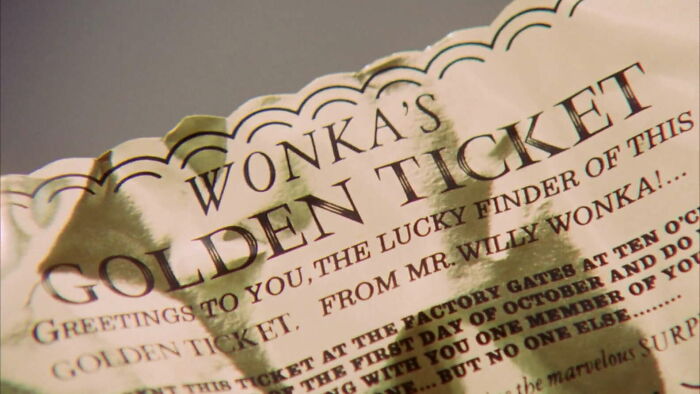

#27 The Golden Ticket, Willy Wonka & The Chocolate Factory (1971)

Julie Dawn Cole, actress (Veruca Salt): “They were made of a kind of foil paper, I suppose, a foil-covered paper. They were sort of crunchy, but more substantial than a piece of cooking foil. You had to be a little bit careful. The props men would hand them to you with great reverence: ‘Here is your golden ticket.’

“We got to handle them twice, because we got them when we found the ticket, in whatever scene that was, in September 1970, and then when we went through the factory gates. As we were going through the gates, it was always like, Be very careful and don’t lose this. You’re sitting there, holding this thing for ages during shooting, getting a bit bored, thinking, Oh, I better not crease this too much. So I think the one going through the factory gates, by the time it got to the gates, was probably a little dog-eared. That’s why they had spares. The actual going through the factory gates, that whole scene, I think we were a week in shooting it, a week of holding onto this one piece of paper.

“The props men would appear and disappear mysteriously, a bit like Slugworth, with the tickets. I would imagine there were a couple hundred made. I had about 10 at one time, and now I still have one framed with a Wonka Bar. I don’t think the movie industry recognized the importance of props back then. Nobody did. They were just things that were in the movie. Movies didn’t have this longevity and cult status yet. It’s still a fairly young industry.

“But this prop has gone down in pop history. People refer to it as, ‘Well, he got the golden ticket!’ If you hear that on a program, you know where it came from, from Willy Wonka. It’s turned into a catch phrase. It’s extraordinary.”

Image credits: Thrillist Entertainment

With so much effort going into props, it’s no wonder they become so iconic. Some end up in museums, some are auctioned off for staggering prices, and others? Well, they’re sitting in an actor’s home as a prized memento.

Which of these movie props would you love to own? Let us know in the comments!

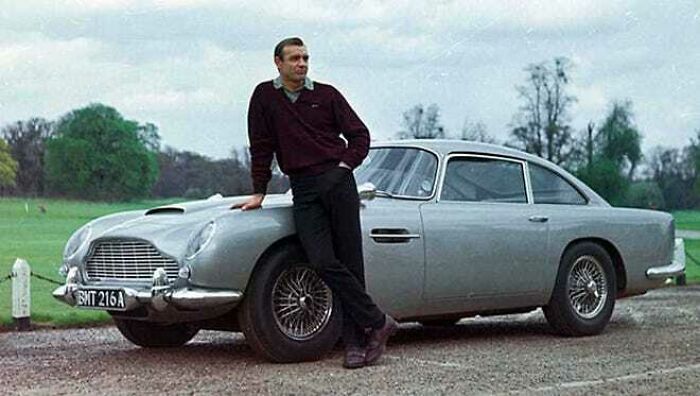

#28 The Aston Martin, Goldfinger (1964)

Bond’s original Aston Martin DB5 is not just a car; it’s also a spy gadget. It’s equipped with bulletproof windows, revolving license plates, machine gun front fenders, tire cutter wheels, and even an ejector seat. The world’s most famous spy car is estimated to be worth about $4 million. The only problem is that it’s been missing since 1997 after being stolen from an airport hangar in Boca Raton, FL.

There was an extensive search for the famous Aston Martin, but it’s feared that the car may have disappeared forever.

Image credits: Ann Casano

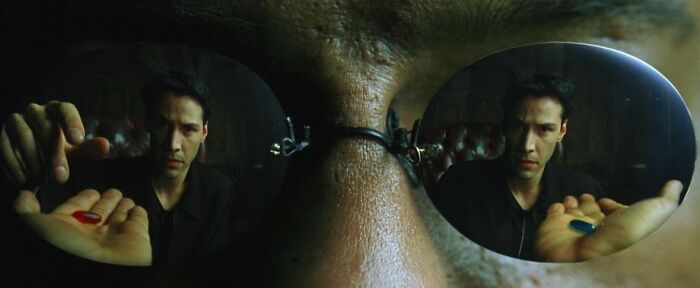

#29 The Red And Blue Pills, The Matrix (1999)

Owen Paterson, production designer: “Lana and Lilly [Wachowski] are true geniuses… I would have specific conversations with them about that scene. It takes place in a hotel that is essentially closed down. It’s derelict. They had this beautiful expression [for it], which was ‘putrid decay.’ “I can’t remember what was in the pills, but there were discussions with doctors, so if anyone had have swallowed them by mistake, then it would be safe. It was just something that had to be blue and something that had to be red — I believe we used gelatin caps. It was quite simple the way that was set up. The other really interesting thing was there were certain shots [in the scene] that were physically impossible to do. One is in the spectacles that [Morpheus] is wearing, you’ll notice the left and right hand — and I think the right hand is the red pill and the left hand is the blue pill — but they are held up to the eye… The scene was shot so that the two separate hands were shot and both placed into those glasses. You would never know.”

Image credits: Nathan Johnson

#30 The Red Stapler, Office Space (1999)

Mike Judge, director: “I wanted the stapler to stand out in the cubicle and the color scheme in the cubicles was sort of gray and blue-green, so I had them make it red. It was just a regular off-the-shelf Swingline stapler. They didn’t make them in red back then, so I had them paint it red and then put the Swingline logo on the side. “Since Swingline didn’t make one back then, people were calling them trying to order red staplers. Then people started making red Swinglines and selling them on Ebay and making lots of money, so Swingline finally decided to start making red staplers. “I have the burnt one from the last scene. Stephen Root has one that was in his cubicle. There were three total that we made. I don’t know where the third one is.”

Image credits: Nathan Johnson

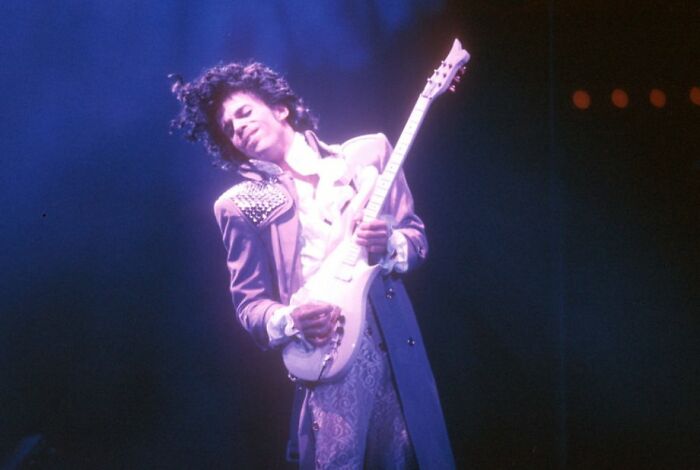

#31 The Guitar, Purple Rain (1984)

Dave Rusan, guitar maker (in an interview with Premiere Guitar, 2016): “Prince wasn’t much for small talk. He could certainly express himself if he felt it was necessary, but in this case he didn’t all that much. So he had this bass with him in the store that day — I’d actually worked on it before — and his main requirements were just that the guitar should be in that shape, and it had to be white, and it had to have gold hardware. I think he specified he wanted EMG pickups, but compared to all the conversations you would have with somebody about a custom guitar, there wasn’t anything else he wanted to talk about — the size of the neck, the frets, the playability features, or anything. He did come in once after that, and Jeff [Hill, the owner of Knut-Koupée Music] was able to get him to make a few comments, but I figured if he’s not going to tell me what he wants, I’ll make something I think he’ll like and hope for the best.”

Image credits: Nathan Johnson

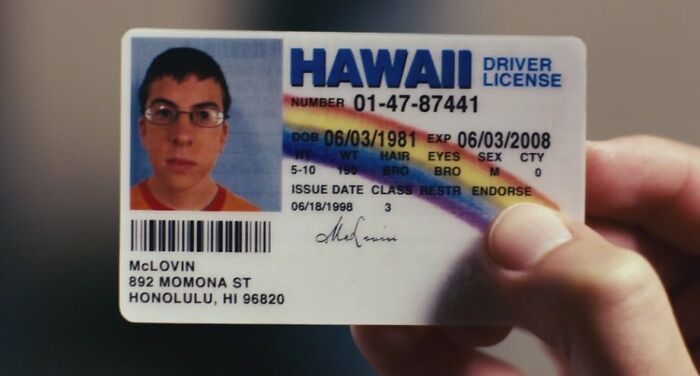

#32 The Mclovin ID, Superbad (2007)

Chris L. Spellman, production designer: “I was doing the film Knocked Up with Judd Apatow [who] said he had this other film that he was producing and that he’d like me to meet on it and read the script. I really laughed out loud a number of times. I remember reading about the guys trying to get alcohol and Fogell getting a fake ID. I don’t believe it was really descriptive, I think it just said he brought out a fake ID and that his name was McLovin.

I don’t believe it said that he was from Hawaii. I actually mentioned to the guys, why don’t we make his license from Hawaii [because] I had done a film there and I just thought about a state that’s not even in the mainland. I remember researching streets because we had to put a street name on there.

“The guy that created it was our graphics designer named Ted Haigh and I brought him on the movie because he has a website called Dr. Cocktail and he knows more about the history of cocktails and alcohol than anyone I’ve ever met. I knew that we had to create all these alcohol labels, because the kids were under 21 and we had to create fictitious labels. So I brought Ted on, mainly to do the liquor labels and stuff. Sometimes the best part of working with Seth and Evan is actually making them laugh and hearing them laugh. I recall Seth laughing and saying, ‘Yeah, let’s make him from Hawaii.’”

Image credits: Nathan Johnson

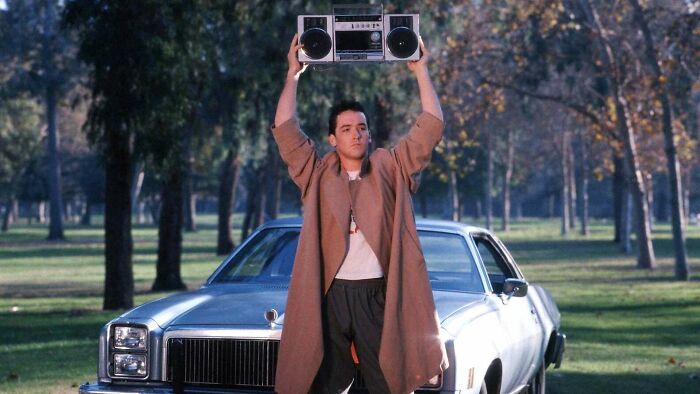

#33 The Boombox, Say Anything… (1989)

Barry Bedig, property master: “Finding the right prop can be difficult sometimes. The object of the game is to show the director a lot of stuff. I did a Herb Ross film, I think Steel Magnolias, and we had to find a piece of luggage, so we showed off 150 pieces of luggage. The more you show the more they can’t say no. They have to pick something. So I found a lot of boomboxes. Cameron picked one. And yeah, it was a working boom box, it played. Actually I think the one we got was rented. Just came with a bunch of stuff.”

Cameron Crowe, director (in an interview with Entertainment Weekly, 2002): “[The boombox scene] was the last thing shot on the last day with the last moment of sunlight. John [Cusack] felt that Lloyd was kowtowing too much by holding up the boombox, and that it was too subservient a move. He didn’t love the scene, he didn’t quite understand it yet — he certainly does now — and he wanted to be more laid-back.

“My whole argument was, ‘Be defiant with the holding of the boombox.’ The last take — it was a place across the street from a 7-Eleven on Lankershim in the Valley — he held up the boombox, and on his face is the whole story of the character — the love of the girl, and, I think, John’s feeling that it was a little too subservient but he was going to do it anyway.”

John Cusack, actor (Lloyd Dobler) (in an interview with Entertainment Weekly, 2002): “I wanted to just have the boombox be on top of the car and him sitting on the roof. So I finally did it, but I did it without a look of longing and adoration and love. It was a different kind of feel than either one of us had originally planned.”

Image credits: Thrillist Entertainment

#34 Little Black Dress, Breakfast At Tiffany’s (1961)

Designed by Hepburn’s close friend, Givenchy, the iconic black dress appears in the opening scene of ‘Breakfast at Tiffany’s’ as she steps out of a yellow New York taxi cab. At least 3 copies of this dress are known to have survived. One is in Givenchy’s archive, one is on display in a costume museum in Madrid and one was sold at auction in 2006 for a sophisticated €807,000.

Image credits: Catawiki

#35 Otto Pilot, Airplane! (1980)

David Zucker the co-director/co-writer of Airplane! says the idea started just from sketching a cliche pilot in blow-up form. The art department then created the models that could be connected to an air machine and blown up/deflated as quickly or slowly as the directors wanted. The idea of the “winking” from the doll came from a grip on set, according to Zucker.

Image credits: JD Roberson

#36 The Camera, Rear Window (1954)

Alfred Hitchcock, director (in the book Hitchcock, 1966): “[Rear Window] was a possibility of doing a purely cinematic film. You have an immobilized man looking out. That’s one part of the film. The second part shows what he sees and the third par shows how he reacts. This is actually the purest expression of a cinematic idea.

“He’s a real Peeping Tom. In fact, Miss Lejeune, the critic of the London Observer, complained about that. She made some comment to the effect that Rear Window was a horrible film because the hero spent all of his time peeping out of the window. What’s so horrible about that? Sure, he’s a snooper, but aren’t we all?”

A 1954 ad for the Exakta VX: The choice of the Exakta VX for Hitchcock’s best motion picture could not have been unintentional because of the fact that the VX is the most versatile camera in the world. With it you can photograph any type of subject, microscopic or gigantic, an inch or a mile away. With the VX you can shoot routine pictures with a maximum of simplicity and ease, and master any difficult or challenging subject as James Stewart did in Rear Window.

Image credits: Thrillist Entertainment

#37 The Glowing Box, Kiss Me Deadly (1955)

Robert Aldrich, director (in an interview with Sight and Sound, 1968): “The scriptwriter, A.I. Bezzerides, did a marvelous job, contributing a great deal of inventiveness to the picture. That devilish box, for example — an obvious atom bomb symbol — was mostly his idea. To achieve the ticking and hissing sound that’s heard every time the box is opened we used the sound of an airplane exhaust overdubbed with the sound made by human vocal chords when someone breathes out noisily.”

Image credits: Thrillist Entertainment

#38 The Cigarette Holder, Breakfast At Tiffany’s (1961)

Robert McGinnis, poster designer (in the book Fifth Avenue, 5 A.M., 2010): “The art director told me that all they wanted was a single figure, just this girl standing, but with a cat over her shoulder, and that she would be holding her long cigarette holder. They sent me a few movie stills to work with and I said, ‘Sure, why not?’…. [The art director] told me they wanted to establish that Breakfast at Tiffany’s was a movie about the city. They wanted a couple embracing with the skyline in the background, which they wanted to contrast with the elegance in the main figure of Audrey.”

Blake Edwards, director (in an interview with The New York Times, 1960): “Even Capote is happy about the script. He wrote the producer that we should watch the two-foot cigarette holder and not come too close to Auntie Mame, but he thought we had Holly right, and that was the main thing. I couldn’t agree more.”

Image credits: Thrillist Entertainment

#39 Bubo, Clash Of The Titans (1981)

Ray Harryhausen, producer/visual effects director: “Bubo was in the first version of the script that [screenwriter] Beverley Cross showed me around the time of the release of Sinbad and the Eye of the Tiger [1977]. I had always wanted to do the story of Perseus and the Gorgon, but I could never work out a coherent continuity. Beverley Cross was a Greek scholar, and the owl was a familiar symbol, even used on the ancient coins, so he weaved it into the story as a guide to Perseus. I worked on the design for quite some time, trying to keep it simple and practical, but beautiful in its own way. As far as the noises he makes, what other sound would a mechanical owl make?” Steven Archer, first animation assistant: “Ray’s main instruction to me was to give the figures rounded movements. Occasionally he would tell me to do more of this or less of that, but overall he seemed pleased with my work. The first animation I did was the flying sequences with the tiny Bubo figure, shot against a blue screen. Most people just wouldn’t realize the sheer physical hard work of doing such scenes, with the figure on wires several feet above the stage. I would have to climb a ladder, move the model, climb down and take the ladder away, walk back to the camera and hit the exposure pedal. Then repeat the thing all over again and yet again later when working with the vulture. Doing that day after day was totally exhausting.

“Ray spent a day going through the problems I might face using the rear-screen set-up, and then I also sat in the background for a couple of days just watching him animate. At least the Bubo figure was a lot easier to handle. I had a little trouble with relative size to the background plates and had to re-shoot a few sequences, but it was all part of the learning process. There are so many things you have to consider with the technical aspects, let alone concentrating on the animation movements. It just makes you realize just how brilliant Ray was as an animator.” Quotes courtesy of Mike Hankin, author of Ray Harryhausen: Master of the Majicks

Image credits: Thrillist Entertainment

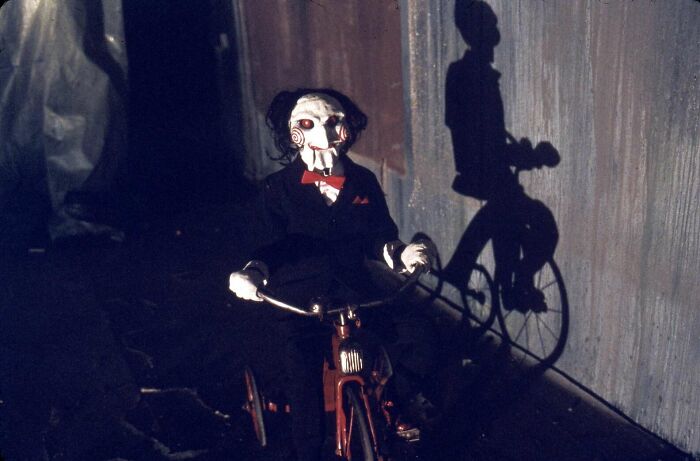

#40 Billy The Puppet, Saw (2004)

James Wan, director: “Billy was built in my apartment back in Melbourne when I made the [original short film]. I made it from clay, ping-pong balls for eyes, and newspaper wrapped together — all hidden underneath a cheap, kid’s suit. Who the fuck makes suits for kids? Here’s a morbid thought: they’re either for weddings, events, or funerals.

“When Leigh [Whannell, writer] and I were gearing up for the feature, we thought we would get the Hollywood version, and it would be remade with animatronic and state of the art shit. But the movie was so low budget, the producers just said, ‘use that again’!”

Image credits: Thrillist Entertainment

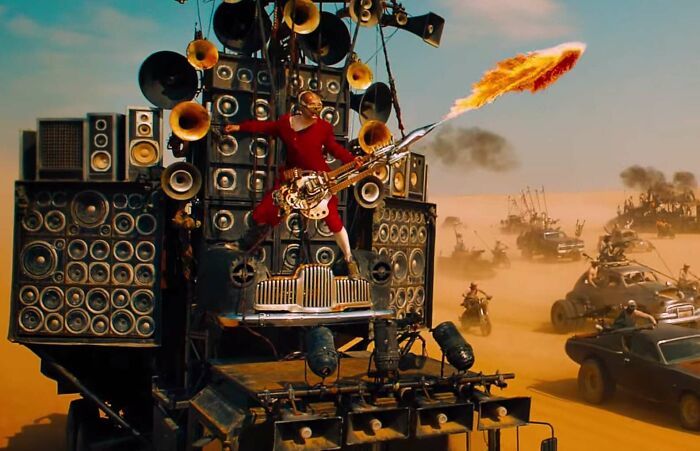

#41 Coma The Doof Warrior’s Guitar, Mad Max: Fury Road (2015)

Matt Boug, salvage artist: “The guitar, 100% designed and created for the movie, came from the concept of music being used in war. The warlord character, Immortan Joe, needed a musician to rally his troops. Who better in the wasteland than a heavy metal guitarist? It was reminiscent of the helicopter sequence in Apocalypse Now, with the chopper pilots playing Wagner’s ‘Ride of the Valkyries.’ It’s symbolic of the corruption of power, a musical instrument being used to fight the oppressed.

“George Miller, the director, had given the project to sculptor Michael Ulman, who had been hired to help create objects for the film in a junkyard aesthetic. The theme of recycling and re-purposing objects was a major part of the design language — making the absolute most out of the remaining stuff that was around was an essential part of life in a post-apocalyptic world. And who doesn’t want a flaming guitar that can kill people? So Ulman created a version of the Doof guitar as a sculptural piece out of second-hand metal scrap. Some of the objects he used included car horns, trumpet parts, and a bedpan.

“My job, then, was to take the sculpture and make it durable for a year in the desert whilst being dangled from a truck in a sandstorm. It needed to function as a real guitar so that iOTA, the Doof actor, could play tunes onset for his warboy comrades. It also needed a fully working flamethrower. To make it all work, I needed to build a chassis for the guitar — just like a car. I transplanted the electrics from a pre-existing double-necked guitar into the new Doof guitar chassis I built, and, after much swearing, bolted on the bedpan cover. I got an old guy in the slums of Namibia, Africa, who restored guitars, to help me with the electrics. He was a bit perplexed with the design: ‘Do you play shit music with this?’ he said, referring to the bed pan.

“Making the whole thing work musically was the hardest part — getting the bridge distances and angles right so the guitar would stay in tune whilst being thrown around and left in the sun. But the day we finally plugged it into an amplifier and strummed the first notes of Chris Isaak’s ‘Baby Did a Bad Bad Thing’ was a happy day indeed. iOTA complained a lot about how shit the guitar was, but everyone else fucking loved it and lost their minds over it.”

Image credits: Thrillist Entertainment

#42 The Brass Balls, Glengarry Glen Ross (1992)

Jane Musky, production designer: “Props had many tryouts and ended up with the set Alec [Baldwin] was comfortable with. We all decided they had to be big enough and intimidating enough and brass, for sure, but not too big or small, as to be silly. The sound of them hitting is what sold the gag. The brass balls also had to fit in his briefcase with the steak knives. If I am remembering correctly there were some laughs at first [during shooting], but, with such a wonderful and skilled cast, once the scene clicked it was dead silent and serious.

“On Glengarry the prop master and I spent quite a bit of time developing the dressing and propping inside each salesman’s desk since they were at these desks for days on end. Opening and closing drawers. Using the contents during filming. The first day the actors came to the set it was a thrill to see this incredible ensemble sit at their stations and spend about 20 minutes going through the drawers and file cabinets smiling. Each gave us a small list of additions and we were on our way. That office set lives in my memory as one of the great thrills of my design career.”

Image credits: Thrillist Entertainment

#43 The Dental Pick, Marathon Man (1976)

Guy Bushman, assistant property master (in a letter of provenance written for auction): “[Cinematographer Conrad Hall] wanted a white power cord for contrast on-screen. The real black power cord was hidden in Olivier’s sleeve while a vestigial white cord was added for effect.”

Jim Clark, editor (in Dream Repairman: Adventures in Film Editing): “The sound effect of the drill was crucial to the effect we desired. As the drill came closer and began to go out of focus, we altered the pitch of the drill, as if it were boring into something hard. The sound continued until the camera panned to the white light when the drill stops and [Dustin Hoffman’s] scream is heard. The out-of-focus image was created in the optical printer, as was the zoom into the white light.

“The astonishing thing about this scene is that it remains potently arresting while not being visually emphatic. Very little is actually shown. Originally there was another section that was much more graphic. I did suggest to [director John] Schlesinger that we should shoot some very close inserts of the drill touching the tooth. He did not think this was at all necessary but allowed me to shoot some material. I spent some time getting the special effects people to produce a whiff of smoke as the drill hit the tooth. I thought this was really good, which shows how insensitive I had become to the power of this sequence. The graphic inserts remained in the film for a long time and were there for the first preview without causing the audience to faint.”

Image credits: Thrillist Entertainment

#44 Boy With Apple, The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014)

Michael Taylor, painter: “[Wes Anderson] kept sending me different images. Italian Renaissance paintings, but also some Germanic stuff, like Hans Holbein and Lucas Cranach. He had chosen the name of the artist: I was ‘Johannes Van Hoytl,’ which seemed to suggest to me a Dutch painter.

“I started off with that hand holding the apple, with the fingers up. I’ve always wanted to do that, because there’s this painting of Henry IV’s mistress with her sister. They’re both nude and one sister is holding the other just like that, by one nipple. It’s a very striking and strange image. I needed something that would be recognizably different, [so it wouldn’t] look like just any other Renaissance imitation painting. I painted it in a private school, a beautiful old building in Dorset. The studio found the model. On and off I painted for four months. After about two months, Wes was starting to get a bit anxious about what it looked like. So I sent an image and it wasn’t exactly what he wanted. There were a few things that got painted out. There was a bird skull on a pewter plate and a picture of a castle. We kind of simplified it. I have no idea where it is now. It’s the funniest thing when you do paintings. You have a very intense relationship and then they go off into the world and have a life of their own.”

Robin L. Miller, property master: “When that thing arrived in Berlin, it was so heavily crated it could have been a Rembrandt. It hung every day in Wes’s apartment. When we shot it, we would send someone to go get it — he loves his props. Then there was the other painting, Two Lesbians Masturbating. He wanted it to look like an Egon Schiele, in that style. And they found a kid at a [Wes Anderson-themed art exhibit]. They went from a portrait artist to a guy who was just a solid Wes fan.

“Now Boy with Apple was an original size, we see it on the wall, but (and Wes knew that we had to do this from the beginning) for all the scenes of it being run around and the wrapping being torn off, I made a copy of that that was a third smaller. You’d never know it. It had to fit under peoples’ arms. Movie magic.”

Image credits: Thrillist Entertainment

#45 The Umbrella, Singin’ In The Rain (1952)

Gene Kelly, director-actor-choreographer (in Gene Kelly: A Biography, 1974): “I was running through the lyrics of the song to see if they suggested anything other than the obvious when, at the end of the first chorus, I suddenly added the word ‘dancing’ to the lyric — so that now it ran ‘I’m singin’ and dancin’ in the rain.’ Instead of just singing the number, I’d dance it as well. Suddenly the mist began to clear, because a dance tagged onto a song suggested a positive and joyous emotion… All that was left for me to do was to provide a routine that expressed the good mood I was in. And to help me with this I thought of the fun children have splashing about in rain puddles and decided to become a kid again during the number. Having decided that, the rest of the choreography was simple. What wasn’t so simple was coordinating my umbrella with the beats of the music, and not falling down in the water and breaking every bone in my body. I was also a bit concerned that I’d catch pneumonia with all that water pouring down on me, particularly as the day we began to shoot the number I had a very bad cold, and kept rushing out into the sun to keep warm whenever I could.”

Image credits: Thrillist Entertainment

#46 The Closet Computer, Clueless (1995)

Amy Heckerling, director: “Each day they go through outfits and they see what goes with what. It seemed like there’d be a lot of repetition and a big waste of time. Now I used to play with cutout dolls when I was a little kid, and I thought, ‘What if I had cutouts of all my clothes, little pictures, and I could figure it out that way?’ Then when computers came along, I thought you could computerize every garment you have — you could go through everything quickly. It was always something I thought would be a time-saver. I thought that before there were computers.

“[The computer] was something between the costume person, Mona May, and the prop guy had to make it feel like what it was. We photographed Alicia [Silverstone] so you could see the clothes coming on to her. A computer expert who came in [described] exactly how it would go, swirling and swiping with her hands, how the outfit would come on, that was created by the computer guy.

The designs are not realistic. When I wrote it, before we shot it, early ’90s grunge was a big thing and it was an anti-fashion moment. Then big designers started cashing in on it. Suddenly you have an expensive plaid outfits. In Seattle they wear plaid as a practical, keep-warm, don’t-care-about-what-you’re-wearing feel.”

Image credits: Nathan Johnson

#47 The Portable Memory Eraser, Eternal Sunshine Of The Spotless Mind (2004)

Dan Leigh, production designer: “Our mission was to arrive at a believable piece of medical equipment that did not appear futuristic. The character of Dr. Mierzwiak (Tom Wilkinson) maintains his practice on the fringe of medicine. His office is decidedly low-tech and a bit shabby.

The memory erasing apparatus had to belong with that character in that environment. “Design began with a visit to the neurosurgery department at Mt. Sinai Hospital in Manhattan where we were shown an array of electrodes, wires, and monitors. Film ‘time’ would not allow for the painstaking one-at-a-time application of electrodes so we needed a framework. [Director] Michel Gondry has a fascination with the common kitchen colander and we began fusing ideas together. The colander gave us a one piece framework to attach many electrodes together and retained the low-tech style and necessary portability.“

The next consideration was Jim Carrey’s comfort. Neck and head support was added to the design to keep him comfortable for extended or repeat takes. The added design elements were carefully referenced to actual medical equipment, and points of light used to indicate the helmet was operational. These design elements were fabricated and assembled at Costume Armor in Cornwall, NY, and sent out for automotive finishes. Two of these were made but only one had an approved finish and became the hero prop. Both have vanished into movie lore.”

Image credits: Nathan Johnson

#48 The Red Balloon, The Red Balloon (1956)

Pascal Lamorisse, actor (Pascal) and son of director Albert Lamorisse, in an interview with NPR (2007): “It’s a love story. This poor little boy, we’ll call him Pascal, he seems to have a grandmother. No sisters, no parents, and his only hope in life, his only real, close friend, is the red balloon. The red balloon was my friend. He was really like a real character with a spirit of his own, because he was glossy and reflected the world around him. It looked beautiful. You don’t see balloons like that.”

Image credits: Thrillist Entertainment

#49 The Kobayashi Porcelain Mug, The Usual Suspects (1995)

Howard Cummings, production designer: “What I really didn’t know until we started getting into it is that Bryan [Singer, director] wanted all the clues in the room. So we started thinking, What could these different things be? We’d all stand around and argue about what [Kevin Spacey’s character, Verbal Kint] should look at.

“The cup, though, was the scripted centerpiece of it all… It was a breakaway mug. But they don’t really hold coffee well, so we had to find a matching mug. I can’t remember if we picked the mug based on what we could find in breakaways or if we actually had to make a breakaway mug. I didn’t realize Bryan was going to do an ultra, ultra close-up. And there is no Kobayashi Porcelain. You can sort of see in the close-up that it’s stamped on and I am sitting here cringing, going ‘Nooo.’ Getting it to break, I remember I had to break a few. It was coincidental that in the floor shot it broke looking the right way. But we had to break several so the name was readable. And that [mug] had to be real because you could see the edges of it.”

Image credits: Thrillist Entertainment

#50 The Eggs, Alien (1979)

Roger Christian, art director: “The eggs were made with grips underneath where you could pull and open them up. Everything in H.R. Giger’s world is combined with female or male body parts, so the eggs had to look menacing and sensual at the same time. The membrane is a sheep’s stomach — I know, because I had to buy stuff from the abattoir all the time (or I’d get my buyers to go). To get that burst out, the only way to do it, Ridley [Scott] had to put on a rubber glove and put his hand up and chucked it out at the camera. That was the only way to get it to work. [The eggs] were heavy and there were only a few made practical. The rest were background ones, which they made a lot of.”

Image credits: Thrillist Entertainment

#51 Leg Lamp, A Christmas Story (1983)

This bold lamp was brought to life by production designer Reuben Freed for the film adaptation of a story by author Jean Shepherd. Because the lamp was Shepherd’s own creation, Freed had no idea what it would look like. Legend has it, Freed illustrated what he imagined it would look like and Shepherd approved it immediately.

When it came to fabrication, Freed used a mannequin’s leg because the lamp had to be big enough to see across the street. He then borrowed fishnets and a pump from the costume designer to give it a “bad girl” look. Freed created three versions of this lamp for the movie, but unfortunately all three originals were broken in the film.

Image credits: Invaluable

#52 The Tennis Racket, The Apartment (1960)

Jack Lemmon, actor (Baxter) (in Lemmon: A Biography, 1975): “Working with Billy [Wilder] I began to understand ‘hooks’ — those little bits of business that an audience will remember, sometimes long after they’ve forgotten everything else about the picture. The key was a ‘hook.’ For ten years after that film, people would still come up to me on the street and say, ‘Hey Jack, can I have the key?’ Another was where I strained spaghetti, using a tennis racket for a colander… Today, one of the first things I look for in a script is the hook, that little audience-grabber.”

Billy Wilder, writer-director (in Conversations with Wilder, 1999): [The spaghetti-strained-through-the-tennis-racket idea in The Apartment began with an innocent comment by co-writer Izzy Diamond: “Women love seeing a man trying to cook in the kitchen. Then we both set about trying to find the perfect situation that shows] how a man tackles a problem with a missing kitchen object. It was obvious that it was his apartment — you know, he just never cooked. Or he just bought himself a sandwich or something, on the way home. But there I did not have a sieve, you know. So I don’t know whether it was [Diamond] or it was me, but it came kind of spontaneously. For macaroni or spaghetti, we need a sieve, So I said, ‘Let’s have a tennis racket.’

Image credits: Thrillist Entertainment

#53 Zuzu’s Petals, It’s A Wonderful Life (1946)

Karolyn Grimes, actress (Zuzu): “I’m sure they threw it away. It was a flower! I know it was burgundy colored — a really beautiful burgundy color rose. I remember that, but I’m quite sure it was thrown away. The movie wasn’t a success when it came out so it wouldn’t have been anything great to hang onto anyway. It was just a movie and no one thought it would ever become what it is today. No one knew. So all of the props were pretty much destroyed in the ’50s. That’s the way it goes. But this is one of the most beloved movies of all time now.

“It was something I never dreamed would happen. I never even saw the movie until I was 40. Now I live it, eat it, drink it, sleep it, and I have a wonderful time meeting people and traveling and sharing it. And, oh my goodness, they share with me their feelings and their thoughts about the movie and how it’s helped them through life.

“Since 1980, It’s a Wonderful Life has been a huge part of my life. Everyone remembers Zuzu’s petals. When we actually filmed it, I saw Jimmy Stewart put the petals into his pocket. I’m sure [the director] Frank Capra shot it several times, and I don’t suppose I was watching him put the petals in his pocket with each of the scenes that he shot, but he kept it in there. So I have to think he did it for a reason. I think that he put it in there because he wanted to show that Zuzu loved her daddy very much but she knew he wasn’t perfect.

“It’s an integral thread throughout the movie. When George Bailey is in the unborn sequence and he’s downtown and it’s all crazy down there and he jumps in Ernie’s cab, he says, ‘Hurry, Zuzu’s sick.’ So she’s mentioned there and when he comes out of Martini’s he looks for the petals and they’re not there. It’s a thread that runs throughout that unborn sequence. It showed how much he loved that little girl and how much he loved his family and how fortunate he was to have his family. So when he found those petals when he came back to the born sequence again, it was such a joy to him.”

Image credits: Thrillist Entertainment

#54 Spaceballs: The Flame Thrower, Spaceballs (1987)

Dennis Parrish, prop master: “Mel [Brooks, director] wanted ‘Spaceballs: The’ everything. He left it to me to go crazy with. He loves creativity. I came up with about twice as much as was scripted, and the last was the flamethrower. It was the type of stuff you see at a store when you go to Disneyland or if you go to another state, like a Wyoming keychain or a Wyoming ashtray. Merchandising! Movies being all about merchandising. Sometimes they really are.

“[The flamethrower] was a weed burner and we made it a little bit more… powerful. But I got it out of a catalogue and adapted it to make it into a flamethrower. We were very careful with it, and Mel did it while on his knees playing Yogurt, which complicated it somewhat, but we rehearsed for awhile before we put the flame to it. He did it!”

Image credits: Thrillist Entertainment

#55 The Mask-Maker, Mission: Impossible III (2006)

Syd Mead, concept artist: “If you remember the TV show, at the end of the episode they strip off their masks on one of the core characters. In [J.J. Abrams’] mind he was like ‘How did they get the mask? How do you know it’s going to match the character they’re trying to impersonate?’ He gave me the task of designing a mask-maker to be used in the field in real time.

“The way you start, if you’re going to make a mask that’s going to be pulled over somebody’s head, obviously it needs to be in the shape of the head. The head they used was actually a scan of Tom Cruise. So you open the cabinet and you slip a polyurethane mask over the head. The first pass — that’s going to be the laser, and that pours in minor skin details and pores. And the second pass is an ink jet printer. Also J.J. said it’s carried around by people on the team, so I made it with a sort of military-grade look — it looked like it had been used and abused. I gave J.J. the finished sketches [of the mask-maker] so he could hang it in his office.”

Image credits: Thrillist Entertainment

#56 The Alarm Clock, Groundhog Day (1993)

Amie McCarthy-Winn, prop master: “It was the first [movie] that I ever prop mastered. I worked with really good people. I remember one thing that Harold [Ramis, director] said to me, and I’ll never forget it. I had a ‘show and tell’ set up, where I lay out props. I’m walking him through the room and the minutiae of props, and I said, ‘Is there anything I should know from you on what you’d like from my department?’ He laughed and smiled and said, ‘I just want the props to work.’ I’ve never forgotten that. There’s nothing else I want either.

“At a production meeting, they decided they wanted a digital clock, but there were issues with the lighting of it. So they went to a little older fashioned: the flip. So I went out to prop houses in California and got samples to show to Harold and the producers. I think we found ‘the one’ at a fair in a town outside Illinois called Sandwich, a once-a-month thing where everyone sells stuff. They ultimately say, ‘I like this one,’ and that was well and good, but I didn’t have another in my back pocket. You need multiples. But we found one more — I only had two originals — and I deferred to another prop master for a referral for someone who could make multiples of the clock.

“I think I had eight to 12 of the clocks. There were the originals, and then there were clocks that I made that were rigged to simply go from 5:58 to 5:59 to 6:00. That was another couple I had in my back pocket. A prop maker makes molds of the real clocks, of all the pieces, they measure the numbers — it’s a big megillah. There was a remote control off camera and they’d count down and you wouldn’t have to wait. I also had breakaway clocks that only said “6:00” and had junk inside.

“The most annoying thing to me was, before the movie came out, there were billboards for the movie with Bill Murray on one side, Andie MacDowell on the other, and a clock in-between, and it’s a big clock with bells on the side. Who didn’t talk to who? That’s not the clock! But I had a great experience. We got the [continuity] in the town square down to a science.”

Image credits: Thrillist Entertainment

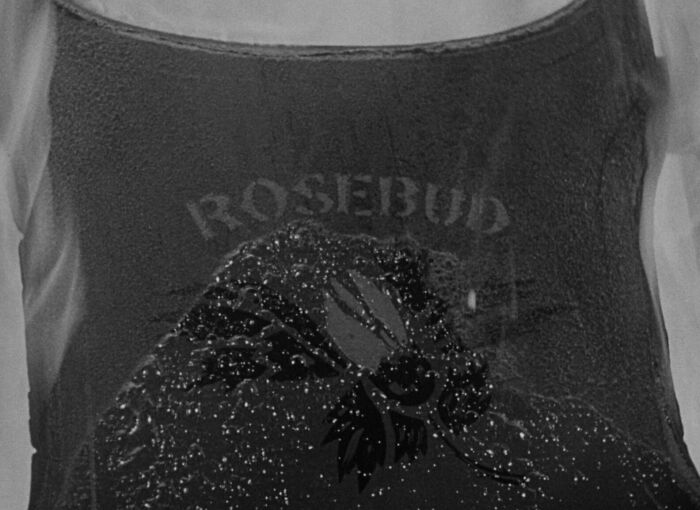

#57 “Rosebud,” Citizen Kane (1941)

Robert L. Carringer, from his book The Making of Citizen Kane (1984): “The original Rosebud sled… [was] custom-built in the RKO property department. It was thirty-four inches long, made entirely of balsa wood, and fastened together with wood dowels and glue. Actually, three identical sleds were built; two were burned in the filming.”

Orson Welles, director (press statement, 1941): “The most basic of all ideas was that of a search for the true significance of the man’s apparently meaningless dying words. Kane was raised without a family. He was snatched from his mother’s arms in early childhood. His parents were a bank. From the point of view of the psychologist, my character had never made what is known as ‘transference’ from his mother. Hence his failure with his wives. In making this clear in the course of the picture, it was my intent to lead the thoughts of my audience closer and closer to the solution of the enigma of his dying words.

These were ‘Rosebud.’ The device of the picture calls for a newspaperman (who didn’t know Kane) to interview people who knew him very well. None had ever heard of ‘Rosebud.’ Actually, as it turns out, ‘Rosebud’ is the trade name of a cheap little sled on which Kane was playing the day he was taken from his home and his mother. In his subconscious it represented the simplicity, the comfort, above all the lack of responsibility in his home, and it also stood for his mother’s love which Kane never lost.”

Image credits: Thrillist Entertainment

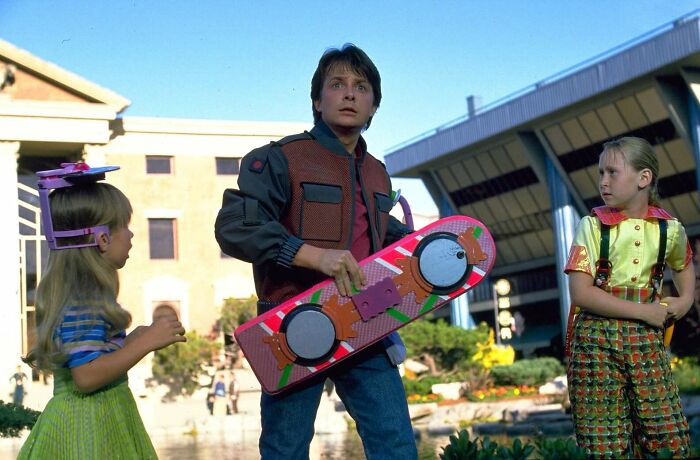

#58 The Hoverboard, Back To The Future Part II (1989)

John Bell, visual effects art director: “[Director] Bob Zemeckis and [screenwriter] Bob Gale — they’re the guys who came up with the thing. I had to visualize what they envisioned. I was working at [Industrial Light & Magic] in 1986 and the project hadn’t officially started yet. But our management came in and said, ‘Bob Zemeckis wants to shoot Back to the Future II, we go to 2015, and there’s something called a hoverboard. Come up with some ideas.’ So I took about a month or so and just started doing random images of different parts of Hill Valley and scenes with hoverboards. We sent down slides to him — because he was now fully involved with Roger Rabbit — and we didn’t hear back for a long time. The next time we heard from him was the fall of 1988. I got pulled into a meeting with Rick Carter, who was the production designer on the film, and he had seen the work I did in ’86 and said, ‘Can we get John to come down to our art department down at Universal Studios for just a couple weeks?’ So I went on loan for what was supposed to be a couple weeks… and wound up being there for four to five months.

“Before I was on loan in the department in Los Angeles, I worked with Steve Gawley and Richard Miller in the [ILM] Highland model shop on the early designs for the hoverboard, which at the time were bigger, more like skimboards or snowboards — bigger, wider, almost like a truncated surfboard. And they had a lot of stuff attached to them, because I’d been paying attention to a lot of skateboard culture in the mid-’80s. You notice how much they modify and personalize their boards, mainly stickers. So I thought in 2015, if these things could fly, maybe they’d put wings on them, different jet engines, they’d soup them up like a hot rod. These early boards were super complex, but when you start getting into production, and you realize they have to make multiples of all these things, it just got too cost prohibitive. The silver lining is that the final version of the hoverboard is so simplistic in its shape, with crazy graphics, that the magic is the power inside of it. You don’t understand it, but you enjoy using it. It’s like a cell phone.

“Rick Carter and I would chuckle about it. We had to put a different kind of thinking cap on this one. We were going 30 years in the future to a place called the Cafe ’80s, but we’re in the 1980s. So what was going to be relevant 30 years from now? Luckily the ’80s were so graphic driven, so colorful, it made that part of it easier. There’s that neon pink. In the 1984 Olympics you had pink and turquoise and peachy gold, and neon was a big driving fashion force at the time. At one point, Swatch was going to be proposed with doing sponsorship for the hoverboard when they were looking at branding for the thing, so we did some drawings with Swatch, and they were bold with colors. But you had to think what would resonate.”

Image credits: Thrillist Entertainment

#59 The Idol, Raiders Of The Lost Ark (1981)